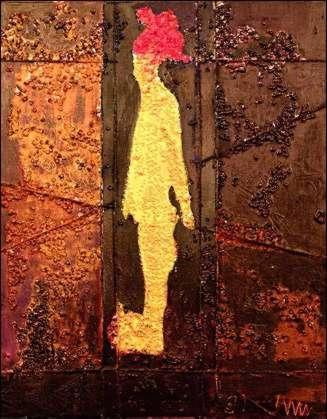

Art by Victor Ehikhamenor

Kath said she had a brother she'd rescued from a bucket of water.

But then Kath said lots of things. She said she knew how to make a shoe float on the river and come out dry and unsunk. She said she knew how to smoke two cigarettes at once. Between her legs.

I knew all that was tosh. You couldn't get shoes to float on the river. Not this one. It was fast and full of wavelets; it ran over stones close to the surface.

Kath said her mum had gone into labour when they were staying with her Nan. Early. That she'd wanted to go up the hospital but they wouldn't take her. That Mrs. Douglas with the walleye was called in instead, because she "did" all the babies in Jehova Street.

I was more interested in the cigarettes. How could you breathe in between your legs? But I wasn't going to ask. Anyway, how did she know? I saw a film once where a cowboy sat by a waterfall and blew smoke rings before killing his best friend. Could you...?

The houses in Jehova Street were joined up, Kath said. Like a kid's handwriting, with dark alleyways between every fourth one. Kath's Nan had four bolsters jammed up against the bedroom window so the neighbours wouldn't hear the screams. That was Mrs. Douglas. Said if the neighbours got meithered, the baby'd be cursed, and she wasn't having that.

I reckoned, when you were grown up, you could just about hold a cigarette between your bottom lips. But. You couldn't walk around with it in there. So what was the point?

Kath said she was downstairs playing marbles on the kitchen floor. With sloes from the tip. The tiles were old and uneven, and the bloody sloes (she swore a lot) kept gathering in one line near the table leg. So she got cross and smashed them. She'd never done that before, and she'd expected dark blue juice.

She could hear the screams. It sounded like three cats on a wall, she said, not her mum. She said she'd never smash a sloe again. It looked like blood on the tiles, and what happened next was probably because of the curses put on the sloes by the travelers.

I guessed, too, if you did smoke down there, you'd have to take it out when you went to bed.

Silence.

Kath said she could hear her own heart beating like it had been switched to her outside and plugged into a wireless. Creaking floorboards. Didn't want to look up at the kitchen ceiling in case there was blood coming down the walls, and that'd be the end of her pocket money. Mercenary, was Kath. And she had a black plait I never saw undone.

She said she counted 100. Fast. And the quiet and the creaking just got quieter and more creaky. And maybe she was making it all up, because maybe she'd been ill and just woken up and it was all a dream.

She said there was a brown velour curtain over the door to the front room with three cigarette holes near the bottom. Velour melts if it's cheap, she said. But she still went and hid behind it because sound carried down the stairs to the front room.

Nothing. Not even breathing.

Then Nan came down all red-faced with her hair sticking out of her hairnet, and only one shoe. Rushed out the back door, came in with a bucket of water. Back up stairs, shoulders all askew.

That, Kath said, was the funny bit. She said you needed to wash down there a lot when you were grown up because it got hairs, and because dirt clung to the hairs. But then, if you smoked down there, why didn't the hairs catch fire? That's what I wanted to know. But the bucket. Why wash out of a bucket when there were perfectly nice china things?

So she waited for the creaks again and went upstairs, matching her footsteps on the steps to the creaks.

And, at the top of the stairs, there was the bucket, outside the bedroom door. Closed. And the pale bottoms of a pair of little feet under the water. And a pale bottom. Upside down. Huge boy's bits showing. Purple under the water.

Kath picked up the bucket and could hardly... And the water was right to the top, slopping down the stairs, and she got the bucket to the kitchen and tipped it up on the tiles, and this little boy slopped and slid onto the floor with the sloe juice. And she said she knew you were meant to slap babies on the back, but there wasn't much point with this one. (Like she'd seen hundreds. See what I mean about telling fibs?)

There wasn't much point because he had a bit of skin all over his face. Just thin. Like rice paper under buns. And his face had gone in the sloe juice. She said she'd cop it something chronic now, so she got the floorcloth and wiped the baby's face.

Now, you see, when we left that school at 11:00, and before I never saw her again—only a few times, as she moved away—she told me the trick with the shoes in the river was to get four balloons. Put each shoe in a balloon, and tie the others so it holds them up. And the balloons they're in keep the shoes dry, and safe.

I met her brother once. Gareth. He came with his Mum to a play Kath and I were in. Looked just like her, too.

I tried smoking a cigarette down there much later. It didn't work.