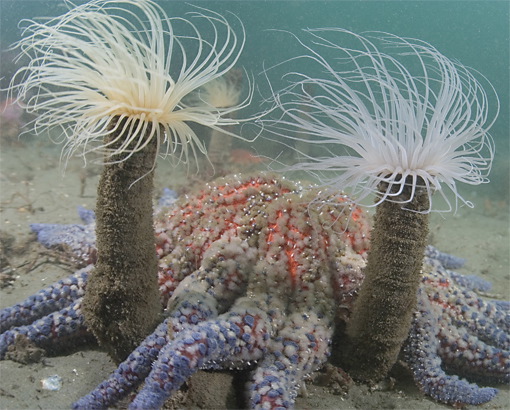

Photography by Kawika Chetron

With consanguineal pride, I welcomed my younger cousin's first forays into the quirky world of creative non-fiction. Following in my footsteps, she evidently looked up to me, respected what I had accomplished. Although "little" Marjorie possessed nowhere near my talent or drive, it was cute to see her try. My benign satisfaction and benevolent sympathies, however, were short-lived.

Marjorie's first published story featured the day-to-day travails of a dauntless schoolgirl terrorized by a bragging, bullying "older brother" with high-functioning autism. In all other respects, the latter's unflattering portrait bore a damnable resemblance to me.

I thought we had long ago extinguished such regrettable incidents like the time I forced her hand inside a burning Easy-Bake oven, but apparently this smoldering resentment was alive and well and living in her overheated prose.

I considered taking issue with her verbally, but concluded it would be altogether apropos if my rebuttal arrived in the shape of a narrative. The recent proliferation of indiscriminate e-zines made it laughably easy to conduct this truculent exchange.

So I wrote of a small girl I knew with trichotillomania who compulsively plucked out her eyelashes, a metaphor for the inner turmoil and psychic damage she'd suffered from years of physical abuse by an alcoholic step-father. Perhaps it was heavy-handed.

Marjorie soon after countered in Poet's Weekly with a thinly-disguised description of a shooting mishap I'd experienced as a kid. It's a short piece, reproduced below, without permission:

Fallen Hunter

Chill breath rises

Boy and dog

Shiver in a duck blind

Marsh's edge

Redwing blackbird

Bobs on drying cattail

Low flying geese

Ignite powder grey sky

Excited retriever

Leaps unexpectedly

Into line of fire

Shotgun reverberation

Ripples the pond

Refuses to fade.

Well, that painful memory certainly wasn't going to fade at this rate. A sore spot, my relatives don't talk much about hunting and family pets when I'm around. You'd have thought she was wearing hip-waders right next to me. Once again Marjorie had crossed the line.

I hit back with the scintillating exposť of a high school teacher with low self esteem who shamelessly boffs her own phys-ed students and any other warm body within groping distance of the shoe closet in the staff lunchroom.

Marjorie was unsuitably inspired, replying via the sordid saga of a skinny pump jockey purchasing his first car on the back of stolen funds from an Esso service station. To her credit, she meticulously compiled the intricate details of a '72 Mustang: the powerful 351 Cleveland engine, low gear ratio and light back end that gave the accursed craft its propensity to slide out of control when accelerating into a sharp turn on loose gravel. Marjorie then reverently recomposed the scattered fragments of an ill-conceived street race. The eerie silence following a collision with a lamp post. The collateral thump of the light assembly falling as an afterthought upon the blue vinyl roof of the car.

So I trotted out the tale of a stillborn birth in the Wainwright obstetrics ward. And how a spiteful Christian nurse misinterpreted the necessary curettage as a prophylactic abortion. The thoughtless hospital caregiver, underscoring her disapproval, flashed a vial of bloody scrapings to the childless couple, chiding, "Would you like to see your baby?"

I guess I won. After that, Marjorie quit writing. This I learned second hand. We don't talk anymore.