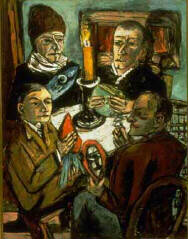

Artists with Vegetables - Max Beckmann

Artists

with Vegetables - Max Beckmann

Essay by Jude Roy

|

Momma was the spanker in the family. She spanked until the sweat flew from her face and we begged her for mercy. Sometimes she used her hands. Other times she used a switch. She would release us and we would writhe on the rough wooden floor of our shotgun shack telling her how sorry we were, over and over again. Then she would send us to the porch for a spell at kneeling until the burning pain in our knees replaced the burning pain on our bottoms. We tiptoed around Momma but we always seemed to find some way to irritate her and incur her wrath. After Daddy died, Momma started drinking and she became even more unpredictable. We were on welfare and Momma's check came to $91.00 a month. With this she was supposed to feed us, cloth us, and provide for us. Of course this became harder and harder to accomplish as she drank more. Soon the bills became a problem, so she drank more. Momma took on odd jobs--ironing, cleaning houses, gutting wild game for hunters--to pay for her increasing drinking habit. Then she discovered that if she went out with men, they would pay for her drinks. When I was about fifteen--my sister was thirteen--Momma went to Ville Platte on a "date." She left my sister and me alone and told us she'd be back around midnight. Midnight came and went and she didn't return. I fell asleep in front of the old black and white television set. My sister woke me the next morning. "Where's momma?" she asked. I didn't know. We walked to the public phone next to Mr. Yo's Saloon and I called the bars in Ville Platte--my sister read the names and numbers to me. Every time I dialed a number, I made a pact with God--"God," I said, "if you let her be all right and in this bar, I will go to church every Sunday. Please, God. Let her be all right." After each failure, I became more and more desperate. "Let her be alive, God," I pleaded. "Let her be alive and I will dedicate my life to you." I found her in the fourth bar I called. An irritated bartender with a harsh, gravelly voice answered the phone. "Yeah," he grumbled into the mouthpiece. "Is Ola Roy in there?" I asked. "She's wearing a blue dress." "She's in here all right," the bartender said. "Been in here all god damn night. Passed out on the table and hasn't moved since." I asked him to try to wake her. I heard him yell out my mother's name--he pronounced it funny, almost Spanish. "Yeah?" Momma said into the phone a few moments later. I could tell she was still drunk. "It's me, Momma," I said. "Madeline and I were worried about you." "I'm the grown up in this family," she spat into the phone. "I can take care of myself." She hung up. I slammed the receiver down and fought back the tears welling up in my eyes. "Is she all right?" my sister asked. "Yeah," I said. "She's old enough to take care of herself and so are we." I softened my tone a little. "Let's go have breakfast," I said and silently broke my pact with God. When we grew too big and too old for Momma to beat us, she found other ways to punish us. Some of her favorites were guilt and embarrassment. My sister's marriage at seventeen was a happy time for both of us--she was escaping, breaking away from the cycle of fear and guilt and hopelessness Momma's alcoholism was causing in us. Madeline was radiant in her white dress. I gave her away in my borrowed suit that was just a little too big for me. I had invited my girl friend to the wedding and I proudly sat next to her. Of course Momma drank too much despite the effort of family and friends to keep her away from the liquor. Before the reception was half over, she sat on a bench in the church hall and bawled loud enough to drown out the music. "Everyone," she cried, "had a chance at happiness except her." Nobody loved her. Nobody cared. Her children were deserting her. They didn't care about her. Even after she had devoted her whole life to them. There was nothing we could do. My sister left for her honeymoon in tears. I stomped out of the reception in anger, my girlfriend running to keep up with me. My aunt and uncle consoled Momma as best they could and drove her home to sleep it off. Not too long after I escaped, too. I enlisted in the navy and requested to be sent overseas. While I was in Spain, I was able to forget about Momma a bit--out of sight, out of mind. She rarely wrote, and what letters she did send were scrawled in her neat sixth-grade cursive and vocabulary about the men she was seeing or blatant lies about the life she was living. My sister wrote more often and more truthfully. Her marriage and subsequent move to New Iberia had not provided her with the curtain she needed to hide from my mother. Momma would not be rid of that easily. My sister tried to conceal some of the more outrageous things my mother did, but she could not keep her attempted suicide from me. Momma was visiting my pregnant sister under the guise of helping her--which usually meant Momma was out of drinking money and needed to hit my sister up for "food" money. We fell for this trick many, many times. Love and guilt will blind even the most determined person. Madeline was determined not to give in this time--she would not perpetuate my mother's sickness. In a fit of self-pity Momma disappeared in the bathroom. My sister heard her sobbing through the door but my mother would not answer nor would she open the door. Finally my sister broke the lock. Momma stood before the sink, both her wrists slashed, blood flowing down the drain like water. "I've got nothing to live for," she cried over and over again. "Nobody loves me." Momma survived. I saw Momma again when I moved back to Louisiana from Boston. She believed that the French language was destined to be reinstated as the official language of Louisiana. "All the young kids are listening to the Cajun music now-a-days. They're going to be talking French again. You watch," she said while riding in the back seat of my sister's car. I sat next to her. We had just been to Eunice to visit relatives. "Momma," I told her. "What's popular is the music. Most of those kids listening to it don't even understand what's being said." "Oh, now you're in college so you know better than your momma." "Louisiana is American, Momma. That will never change again." "Louisiana is Cajun," she said. "Louisiana is Cajun and then American. I hear it in the bars and in the stores and in the houses. You're in College, now. You don't hear what I hear anymore. You watch. They're going to be talking French all over Louisiana again. As sure as I'm alive, it's going to happen again, son." I didn't argue with her. Through the alcohol fumes that clouded her mind and that fierce Cajun pride of hers, she recognized that speaking Cajun made her important. Somebody was listening. They may not understand her, but they were listening by god. Momma died in the back of a police ambulance on its way to a detoxification center in Pineville, Louisiana. She had been arrested the night before for vagrancy and public drunkenness in Ville Platte. After she had a bout with the DT's, the police decided to take her to Pineville. She had a stroke, the coroner said, but any of several other alcohol-related problems could have killed her. My uncle sang at her funeral--his tears and pain flowing out with the lyrics for a sister who never really had a chance in life. I didn't cry--maybe a little--when they put her in the ground. Momma had made growing up a difficult and frightening period for me and my sister, but nothing she did to us could equal what she did to herself. I cried, not because I would miss Momma, but because the only peace she would know and I would know came with death. I dreamed about Momma that night, back in my little garage apartment in Lafayette. I dreamed she called me. "Come with me, son." She spoke in her beloved Cajun language. "Come with me. It's so peaceful out here." A veil separated us, fine as pure silk. It moved with my breath. "I can't, Momma," I told her. She gave me an imperceptible shrug and smiled. Then she disappeared in a sea of hot white light, her arms held out before her, her face softened and peaceful. I awoke then and lay on my pallet on the concrete floor of my apartment and tried to remember the happy moments I had with Momma. I could only remember one and it was a dream. |

Jude Roy was born and raised in Chatagnier, Louisiana to a sharecropper and his wife. He struggled through public school and attended college at the University of Southwestern Louisiana and studied writing under Ernest Gaines. He received his MFA from George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia where he studied writing under Richard Bausch and Alan Cheuse. He is currently teaching at Southwest Missouri State University in Springfield, Missouri. His work has appeared in The Southern Review, American Short Fiction, and National Public Radio among others.

The essay reflects a very small picture of my mother. Alcoholism was a problem she faced and her children faced. There were times when "Momma" was almost normal, but for me they were always tainted with her sickness. I talked to my sister about this and she does not remember her the way I do. As a writer I found that very interesting.