| Jul/Aug 2005 Travel |

| Jul/Aug 2005 Travel |

We are filming on a mountain in Copan, Honduras. We are studying the demise of the Maya population, following the last of the Maya ancestors, trying to glean information about why the civilization fell. To do this, we study those few that are left, the remaining descendents who eek out their existence in ways perhaps foreign, perhaps painfully similar to their ancestors. To learn things, we crawl through sheets of rain on all fours through the mud, but it is different from the way they do it. We crawl as though we are praying to gods, but we are not. We are digging for pieces of clothing, a puzzle of bones and teeth. If the earth has a soul, we are not worried. Standing here among the bones, it is our own soul we worry about as we watch the farmers standing upright on the side of the mountain, trying to farm. The farmer worries about the earth's soul and that of the gods. He knows the earth's soul has never left, even though the soil is fallow, is so scorched even the rain can't soften it. The farmer knows the earth's soul has only perhaps abated, is perhaps resting, but will return.

Who can say that the sun has more strength than the sky that contains it? Or that a man has more memory than the earth that will bury him? The farmer trusts this. I wonder what the earth remembers. And what it will remember of us. Perhaps it is telling us that we are the dead we are looking for. It is said that the dead study the living to see how they do it.

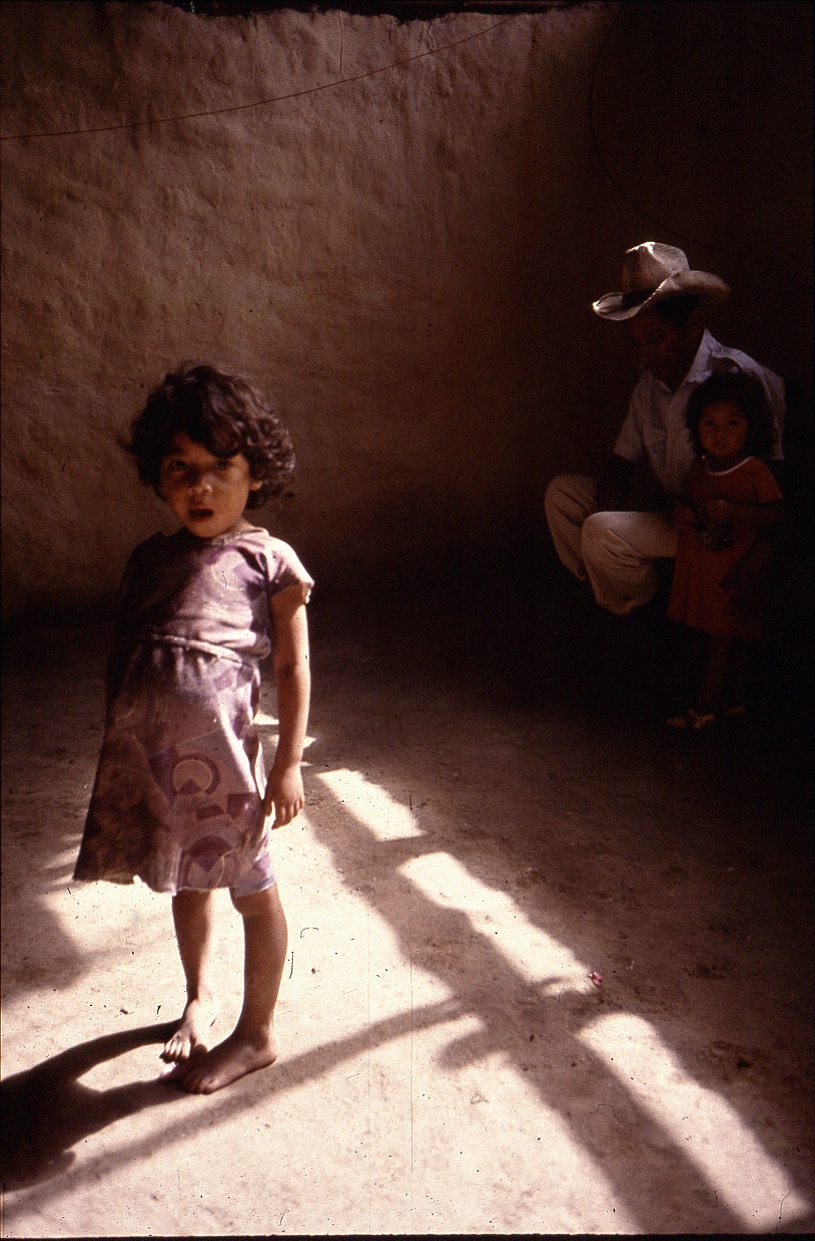

In the hills of Copan, Honduras, the people say that women grow old by the time they are twenty. In the adobe huts of the last of the Maya ancestors, a tattered family still lives in the coveted tradition of survival. The thinnest, smallest woman greets me without lifting her eyes to mine. She reminds me of a branch, so strong it must be brittle, so thin it must be invincible. I believe she is the age of my own mother. My guide tells me she is only 28. Four women stand beside her, three sisters and a daughter. They begin work, their day bent over hot stones, shoulder to muscled shoulder in the sweltering heat, their backs twitching under a veil of thin red dresses as they pound tortillas into the silent air. They hardly look up, even when we turn on our cameras. They allow us to film their dark golden skin as it slickens with sweat, and their soiled threadbare dresses dampening as the day wears on. And yet, I am the only one who notices how their black hair is neatly brushed and tied in ribbons made of the same red material as their dresses, the same strips of threadbare cloth that are wrapped around the left ankle of one of the small boys whose stomach is so swollen with need it makes my hands ache. This is to keep him from running away, through the front door that is held to the hut by another red piece of cloth.

A brief glance from his mother's wet black eyes is all I need. She is telling me without words so I will know how beautiful they all are.

They are beautiful in the way a night empty of stars is beautiful. They are beautiful because they can give you an instant. And that instant is everything. They are beautiful in the way something is beautiful because you know you will never see it again. When the mother finally looks at me a second time, hours have past, but this is the gift. I see that her face is not broken, but woven with rivers that carry silent words from mouth to the eyes, saying everything.

How is it that a boy with a swollen belly wants to laugh and play? And how am I trying to push pen to paper, while the ink is clotting with humility? Make them more beautiful. Make them understood, I think. Or rather, make me understand. Useless are my words.

My words have no place here. Words are not a witness. Only my hands are a witness for they have put the pen down and are now clasped over my heart. This mother smiles at me but has no teeth, and the only emotion I feel is admiration.

I need to know her. To give to her, to be better, stronger, clearer, braver in my words and braver without my words. I watch her face dampen as she feeds the fire, reaching her arms all the way into the oven as though fire has not the slightest influence in this holy space. Against the woman and the fire, I am utterly powerless. What can I give? I tear off my four silver rings and put them in the hands of the young girl who has been sitting by my side for the last two hours. I don't know what will happen. I watch the child staring at my rings, switching them from finger to finger, from hand to hand and back. And then she motions for me to follow her out back into the stony yard where battered hens garble the air to produce eggs. I watch as the girl crouches with two stones, and begins pounding the rings into the dirt until the tiny glimmers of silver have disappeared. She looks at me, scoops up the dirt, sifts it through her fingers. She pushes what is left of the rings into a patch of sunlight to view them from every angle, as they capture every hue. The child buries the rings in the ground for a final time. She takes my hand and points, places a rock over the small mound. What she needs to teach me is that burying is an act of forgiveness.

Click here for more photos.