|

|

| Jul/Aug 2011 • Nonfiction |

|

|

| Jul/Aug 2011 • Nonfiction |

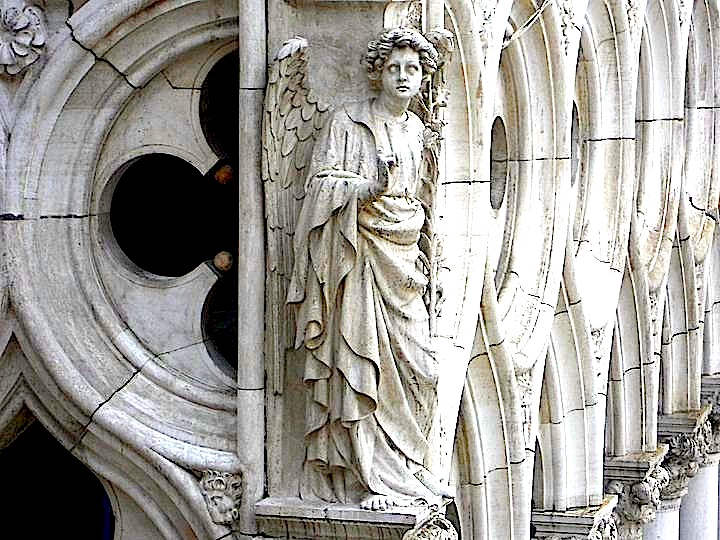

Photo by Sara Caterall

The Duke and Duchess's country house sat outside Chantilly, the site of a great chateau, a racetrack, and several large farms where thoroughbred horses are bred and trained. A smart, updated 19th century mansion with acreage and trees, it had a separate guest house built to match, a garden with a fountain, stables, a large parking area for the expensive cars belonging to their visitors, and a squad of servants. The Duchess's young daughter came on weekends, along with two or three of her school friends. Breakfast and tea were in the English manner, lunch and dinner in the French. I had been brought there by Victor, a producer friend of my husband's, for whom I was writing a screenplay. Russian by birth, a conman by trade, Victor was forever planning movies that might or might not be made but the accompanying publicity assured him invitations to one social event or another. That screenplay would eventually be filmed but not in the way I had hoped. It turned out poorly but occasionally plays on late-night cable television: I avoid watching it for if I do, I always feel humiliated.

On greeting us the Duchess recognized me but did not react to my having been brought there by Victor, merely saying that I should convey her best regards to my husband. She then asked if we needed two bedrooms or one. "Two," I said firmly.

My husband had met the Duchess-to-be during his first sojourn in Paris, when he had written television scripts for an American producer named Shelly. Set in Europe, the series was disingenuously titled "Foreign Intrigue." Shelly had taken the woman as his mistress, he claimed, soon after meeting her on the street in front of the Galleries Lafayette department store where she and her husband were selling third rate men's ties out of an upturned umbrella. Soon he had rented an apartment for mistress and husband, and on occasion was invited to dinner. The conversation, he told us, had always been polite but one evening the husband took offense at Shelly's table manners: when the cheese platter was presented, Shelly cut the nose off the Brie whereupon the husband angrily left the dining room.

As a foreigner operating a legitimate business in France, Shelly needed a French front and so his mistress signed documents, becoming, on paper, the senior partner in the production company. Shelly paid her well for her signature and even more so when she turned out to have an aptitude for chatting up and entertaining actors, directors, money men and their wives, minor aristocrats and the occasional small nobility. The husband faded from view.

Soon she had chatted herself into a position where she was thought of as a television producer in her own right. Invitations came her way; after a while they did not include Shelly. She obtained a divorce which, in those days, was not an easy thing in nominally secular but still Catholic France and very soon, Shelly was no longer by her side except when papers needed signing. Sometime after this, she met the Duke of D.

Their Graces were only recently married: both had brought baggage to their union: he, a crumbling Great House and paralyzing debt; she, the daughter as well as her three other children who I would never meet, and a reputation as an ambitious woman with useful bedmates in her past.

Within minutes of being greeted by the Duchess, I was shown to a pretty little room where I set my weekend bag on a luggage stand and hung my clothing in the armoire. I had packed carefully but after reading the hand-written list of the weekend guests that lay on the writing table and contained a short description of their bona fides, I realized that my casual weekend wardrobe was inadequate. Telling myself that there was nothing to be done about the situation, I went to find Victor, who had left his bags to be unpacked by a manservant. We crossed the lawn and a gravel path to the mansion and entered a salon where several gentlemen were introduced to me, and I to the ladies present. Everyone was smartly dressed in French country weekend clothes, which tended to fine suede and tweed. All were chattering seemingly inconsequentially, some gossiping in phrases filled with innuendo I could not fathom, some talking politics. I looked about the salon and took note of its décor which was determinedly British enlivened with French accessories. Evidently, the Duchess did not want the Duke to feel he was in a foreign land. The day progressed. I listened carefully and, on occasion, when I felt I could, made a statement or uttered a small witticism all of which were politely received. I was much the youngest woman there so the gentlemen eyed me in a socially acceptable lascivious manner, flirted the proper amount and treated me well given the circumstances. We took tea, dinner, drinks. Following this there were cards, music, pairings-off. I retired for the night.

The next day, near noon, the children joined the adults for lunch. They were all about eleven years old, well behaved for their age, respectful of their elders, affectionate to those they knew and earnestly practiced being charming. After a digestive break, some guests went to visit a nearby racing stable, or about their business, while the rest of us repaired to the library or game room. One of the gentlemen present, much the most attractive of the group, took the Duchess's daughter by the shoulders and sat her next to him. In a while, I heard the girl giggling and so turned to look. The man was fondling her, his fingers teasing her as he whispered into her neck. The girl was flustered, plainly aroused and, quite obviously, unaware of what was being done to her and what it meant. I turned back to look for the Duchess and found her seated nearby, watching dispassionately. From his large leather chair, the Duke, too, was watching, turning his eyes away from time to time but then back again, gauging his step-daughter's reactions. By now the girl was hitting the man's shoulder, wriggling on his lap, and kicking her legs. Finally, she pulled away. He let her go, knowing she would return, which she did almost immediately. He embraced her tightly but at that she tore away from him and escaped. I could not tell if it was because she was uneasy at this thing she did not understand or if some other sort of instinct had caused her to flee. Seemingly amused by what had just occurred, the Duchess raised her eyebrows at the seducer before turning to look at the Duke. He appeared somewhat disappointed, although I could not tell exactly what had caused it: the extent of the seduction, or its brevity.

I rose, walked over to Victor, and said, "I'm leaving. Can you drive me to the bus station?" Shocked, he said, "You can't just leave the Duchess of D's weekend party."

"Yes, I can," I said. "I won't stay here." Then I went up to the pretty room, repacked my weekend bag and met Victor at his car. "I told her you were feeling ill and didn't want to spoil the day," he said. "You'll write a note and apologize for not saying goodbye or telling her why you had to leave."

"The hell I will."

"What is wrong with you?"

"Didn't you see what that man was doing to her daughter, touching her all over, stimulating her sexually, and the Duchess allowing it, almost as if she meant to amuse the Duke."

"But, she did," Victor said. "May she rot in hell," I replied.

I waited an hour for the interurban bus. It took four more hours to reach the outskirts of Paris, where I took the Metro. Three train changes later, I was at our apartment. My husband was surprised to see me; his sons from a previous marriage, who were visiting, were openly unhappy I was home: they had been glad to have their father to themselves for the weekend. I left them to their rare enjoyment of him and went to bed. The next morning the boys behaved badly, being confrontational and aggressive toward me, as they usually were, but by then I didn't care. My husband was so taken up with dealing with his sons and their demands that he did not ask why I had returned home so quickly. Several more days passed during which I no longer reacted to their bad behavior and eventually they became somewhat more amenable. When they left, at the end of the month, the younger boy hugged me; briefly, of course, but a hug nonetheless, which I returned just as briefly.

I never again saw the Duchess in person but caught sight of her on television, attending the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer. The Duchess had aged and grown stocky; her hair was less blond than when I had known her and her coronet looked ungainly on her head. The Duke sat beside her in his ermine-tail trimmed robe, his gaze elsewhere, as ever. I later learned that, at her majority, the Duchess's daughter moved to New York where her name gave her quick entree into the world of fashion. She later gave birth to several children, each sired by a different man, none of whom she ever married. Hearing this, I wondered what sort of parent she was and, all those years later, felt a retroactive unease at having taken diplomatic leave rather than attempting to interfere. But at the time, I was too young and they would have thought me boorishly American if I objected to what was merely the sensual initiation of a child.