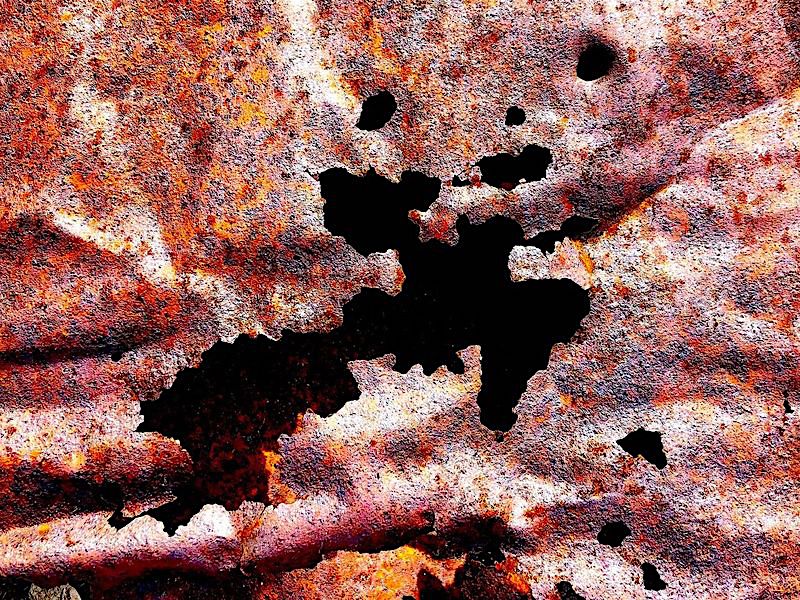

Photographic artwork by Kris Saknussemm

Back home, there is an old bookcase, its red-lacquered wood cracked and scarred. It holds the vintage whiskies my father collects but hardly ever drinks because he "likes the stuff too damn much," and books of course—rows upon rows of ancient tomes, first editions some, from Aesop through Shakespeare to Wilde. They all belonged to my grandmother. As a child I took little interest in the books: to my preteen self they were just part of the furniture. Later in my teenage days, I would open the bookcase when no one was home, pour myself a tipple from the untouched bottles, and sipping the forbidden booze, open the volumes one by one, inhaling their parchment smell, devouring their wisdom. It's the closest I could ever get to knowing her, the real her. Aunt Gabriela once remarked my grandmother was a closed book, but I disagree. She was as open as her upbringing and times permitted her. We just never bothered to read more than the blurb.

Her name was Joanna Kwaśniewska. Kwaśniewska means sour in Polish, but she was anything but. A polyglot, my grandmother was fluent in Polish, English, French, German, and Latin. Although her teaching and translation work brought in only moderate income, she had amassed a wealth of knowledge and devoted the remainder of her life to distributing it. Her room, the second largest in the flat, was a lavish affair with a pink floral poster bed, a matching armchair, a marble table, and a gallery of abstract paintings and nudes of women by artists she claimed were her "dearest friends." The room had not one but two doors, both of which usually stayed open. It was on that pink bed that I was born, having decided to emerge into this world two weeks ahead of schedule, on Christmas Day no less, the year the Berlin Wall fell. When my mother's water broke, our geriatric Maluch car refused to start, taxis were reporting wait times of over two hours, and the ambulances were too busy saving old lives to cater to new ones, so Joanna Kwaśniewska made an executive decision, ordering her daughter-in-law to be moved to the best bed in the house: hers. A nurse during WWII, she proved more than capable in this time of crisis and delivered me into this world with all my toes and fingers intact.

Growing up, I saw countless strangers walk into my grandmother's pink palace, only to be sealed shut for the duration of one hour. I knew they were learning English in there, but the in-camera nature of these meetings lent them all the allure of a secret ritual. Indeed, to a child in '90s Poland, those overheard snippets of English might as well have been magical incantations. Often I would sit with my ear glued to the door, wondering what went on inside. Well, at nine years old, when it was decided my linguistic education should begin, I had to wonder no longer.

"Now open your textbook on page four," Mrs. Kwaśniewska would intone in her immaculate Received Pronunciation, adjusting her chained glasses. "Take it from the top, please."

And like a good boy, I would open the textbook and place my finger on the yellowed page, its ink worn faint by the progress of so many fingers before mine. "Be, was, were." We were: that was one thing no one could ever take away from us. "Find, found, found." She helped me find a language of my very own. "Show, showed, shown." She showed me the way long before I knew I was lost. "Teach, taught, taught." She taught me literature, the groovy kind absent from Poland's antiquated, nationalistic curriculums: T.S. Eliot, Edgar Allan Poe, Oscar Wilde. Initially, the reading material she handed me consisted of Penguin's abridged versions, child-friendly and castrated, but it was enough to whet my appetite. She supplied me the gateway drug and left me a hopeless junky. "Feel, felt, felt." She allowed me to express my feelings in every corner of the world, to every soul, in every room and under every bedsheet. "Wake, woke, woken." She woke me from a long dream, and I've been violently awake ever since.

Other than her students and the occasional interaction with our neighbors, my grandmother mostly kept to herself. The woman could while away long hours in her room, translating obscure academic texts, reading and grading papers to the tune of The Beatles, Maryla Rodowicz, and Jacek Kaczmarski played on her Soviet gramophone. There was only one person who could make her drop all her work in the blink of an eye. Her name was Magda Orłowska.

Mrs. Orłowska, or "Aunt Magda" as I was encouraged to call her, even though she was way older than either of my real aunts, was a constant presence in our household. My grandmother met her during a dinner party at the Polish embassy in Lebanon, where she briefly worked as secretary and translator. Mrs. Orłowska was the ambassador's wife. As they were introduced, it emerged both were from Gdynia and had friends in common. They kept in touch after my grandmother and her husband, the grandfather I never met, moved to London, and reunited when Mrs. Kwaśniewska and Mrs. Orłowska, now both widows, decided it was time to come home.

Although Aunt Magda was my grandmother's age, she couldn't look any more different. While the latter stuck to more conservative outfits, with long skirts, blouses, sweaters and stiletto heels, the other favored jeans and shirts and trainers, often chiding her friend for giving in to "patriarchal oppression." She visited my grandmother on a weekly basis, usually with a jar of Beluga caviar and a bottle of cheap fizzy wine we called "Russian champagne" even though it's made in Poland, saying the liqueur reminded her of her youth. Booze and fish eggs in hand, the two would retire to my grandmother's room, closing both doors behind them. I tried to eavesdrop on these meetings, but all I could hear was loud Polish '60s pop and the occasional bout of giggling that sounded more like schoolgirls than elderly ladies. Once as my grandmother and Aunt Magda were saying their goodbyes, I ran to them and said, "Grannie, are you teaching Aunt Magda English?"

Her eyes twinkling with bemusement, she said, "Now, why would you think that?"

"Because you close your doors. Like with your students. Like with me."

She laughed. "No, Little Fish, I'm not teaching Aunt Magda English. Why, she could probably teach me a thing or two."

"What do you do, then?"

She fiddled with the amber brooch she always wore, a gift from her friend. "You could say we compare notes," she said, smiling.

My grandmother loved the sun, but being sensitive to its radiance, could only love it from the comfort of shadow. So enormous was that love, she sometimes disappeared into herself, became darkness itself. "Come on, Little Fish," she often said in English when we stayed at our summer house, paid for with the few thousand dollars my father earned living on a diet of bread and water in New York—a pittance in America, but a fortune in Communist Poland. "Let's you and I take a walk." And walk we would, I holding her massive handbag, she flitting from shade to shade, adjusting her massive sunhat and the leaf she liked to spit-glue to her nose to protect the jagged scar on its tip.

"How did you get the scar?" I said once as we sat on the old pier, bare legs dangling in the cold shimmering water.

She took a deep breath, her white-knuckled hand tightening its grip on a stick she'd picked up. "A German soldier, a boy, really, grazed me with a bayonet."

"Why would he do that?'

"Anger. Jealousy. They were all jealous people led by a jealous man."

"Is that why you left Poland, Grannie? Were you running away from the jealous people?'

"That was after the war, dear. And we didn't run. Your grandpa received a good job offer. He thought we would all be better off in England. Granted, it was a much more civilized place."

"Do you regret it, coming back?" I said, watching a shoal of fish scatter as I kicked the water.

She sucked her lips and made a mmm sound. "Do I wish I could have tried other things, other lives? Maybe. But regret? No. This is where we are," she stabbed the water with the stick. "And that," her finger traced the newly formed circles and pointed at the distant shore, "is where we will one day be. Keep swimming, and don't look behind, Little Fish, or you might drown."

My English education proceeding apace, I was entrusted to read my first unabridged novel: A Passage to India. I thought it rather dull at the time, and distracted by playing video games, found myself woefully unprepared as I marched to my weekly English lesson. My mind was still busy fabricating excuses when I saw her lying on the floor. She must have been doing her daily exercises, for she lay prone in her night gown, her head propped on hands. Her lips were parted and her eyes wide open, staring at me with something like reproach. But they held no recognition, those eyes. It was as if someone had sucked the life out of them, although it would be more accurate to say life, contained over the years, burst out of her in a great red deluge. To this day I feel guilty about not reading the first chapter of A Passage to India, as if that's what caused her stroke.

My father was on his second delegation to New York at the time, so after the ambulance left with my comatose grandmother and my mother in tow, my big brother and I found ourselves alone. Unable to think of anything else to do, we wandered outdoors and sat in the rusty swings by the forest. Shivering in the fierce winter cold, I asked if Grannie would be okay. My brother, after some silence, said she would probably be a vegetable. The word hit me like a hammer. I didn't say anything, just stared at a group of children sledding downhill. Their joy seemed suddenly distant.

The person who came back from the hospital, escorted by my father, who had taken the first flight home, was certainly not a vegetable. But she wasn't my grandmother either. At least not from a ten-year-old's perspective. Her hair, undyed and unrolled, hung in loose grey wisps. Her eyes, usually sharp as Ockham's razor, had glazed over. Deprived of make-up, her face looked about 20 years older. She smiled and shook my hand as if meeting me for the first time, which in a way she probably was, and hobbled around our house looking lost and bewildered. My father deposited her in front of the TV and put on Keeping Up Appearances, a show she adored and would often make me watch as part of my English education. The moment Hyacinth appeared on the screen, my grandmother burst into laughter. The reaction inspired cautious optimism. But it wasn't clear whether she understood the jokes or simply laughed as a kind of Pavlovlian response. We couldn't know it because the lines of communication were largely down.

Oh, she talked, more than before the stroke. But if the words pouring out of her mouth made sense to her, they were babble to us. It was as if someone had taken all the languages she'd devoted her life to studying, chucked them into a blender, and smashed the ON button. What resulted was a mash of English, French, Polish, and German. There was, granted, some method to this madness. For instance, "katzuszek," a mix of the German "Katzen" and Polish "koteczek," meant "cat." And "ten mały" (the little one) meant yours truly, while "ten duży" (the big one) referred to my brother. But for the most part the only way we could communicate with my grandmother, the great polyglot, was through gestures and pictures. You could sense she, the real she, was somewhere inside there. We simply had no way of reaching her.

Unable to understand her new language, I decided to teach my grandmother one we could both understand. Now, I didn't know the first thing about teaching Polish, but I had plenty of learning material from my English lessons. So gathering all the textbooks and exercise books I could find, I sat with my grandmother, her eyes glued to the thousandth rerun of Hyacinth's shenanigans, and recited the exercise sentences, encouraging her to fill in the blanks, but she just smiled at me and patted my hand. Refusing to surrender, I brought in the portable stereo from her room and put on Peter, Paul & Mary's "Lemon Tree," a song she'd had me memorize. This seemed to attract her attention. Prying herself away from the screen, she laughed and started clapping and humming along. She even tried to sing, but the words didn't come out right. Perhaps conscious of her failings, she sunk back in her armchair and went silent. I grabbed her hand and said, "Come on, Grannie, try again. It took me long to learn, too, remember?" I rewound the tape and stood up, assuming a diva's pose, and started singing away, dancing and hopping in tune and twirling my fingers. "Go on, Grannie, you can do it!" Encouraged, or perhaps endeared by my tomfoolery, she resumed her efforts, this time managing to form some sounds. It wasn't much, but I said, "Super, Grannie, super! You are doing great!" And in the last refrain, lo and behold! Real words poured out of her mouth: malformed, yes, but unmistakably English. "Lemon tree, very pretty," etc. As the music died and the tape stopped, I clapped and cheered. "See, Grannie?" I said, hugging her. "It's not that hard." It wasn't until I turned around that I realized we had an audience. My mother and father stood embracing each other. I thought at first the old man was angry, because his face was screwed up, but then saw the wetness in his eyes. This was the first and only time I ever saw my father cry.

Encouraged by the success, I continued these sessions, now joined by the rest of the family. Through this concerted effort we managed to salvage a fraction of my grandmother's linguistic wealth. It turned out that, unlike Humpty Dumpty (another piece she had made me learn by heart), her mind could be put together again. True, you could still see the cracks and fractures where she'd broken, but we had reclaimed at least a semblance of my grandmother, an abridged version of her. She could now tell us what she wanted without pantomime. I'd been brought up to believe miracles didn't exist, but this was as close as I ever got to seeing one.

The idyll, however, didn't last long. Roughly four months later, while sitting down to dinner, we heard a loud thud from the bathroom. Rushing to the scene, we found my grandmother lying on the floor. Again she was taken to hospital. And again she returned, but this time only a shadow of her former self. She no longer recognized anyone. Gone was any trace of her relearned English. She was perpetually angry now, too, spouting curses in various languages (those seemed to survive multiple strokes). Not that I blamed her. I was fuming, too. We all were. And as a family of ardent atheists, we didn't even have a god to blame.

My grandmother's sickness didn't stop at her. It consumed our family. My father no longer spoke to his sister, Gabriela, who refused to take the convalescent in for a weekend so my parents could enjoy some semblance of normality, and as her state deteriorated, stopped coming altogether. It affected, too, the relationship between my grandmother and Aunt Magda. She visited often after the first stroke, and although they no longer locked themselves in my grandmother's room to compare notes (there was, I supposed, not much left to compare), the woman recognized Aunt Magda, responding to her caresses, smiling and talking at length in her private language while Mrs. Orłowska nodded along, now and then turning away to dab at her eyes.

But after the second stroke, something changed. When Aunt Magda came to visit, my grandmother rose from the armchair and charged the visitor with surprising speed, screaming "Schweine!" and stabbed her in the stomach with her finger. We tried to calm her down. "It's Madzia, your friend. Don't you recognize her?" my father said.

"You crazy or what?" she said, shaking her head at her son and tapping her forehead, then grabbed a kitchen knife from the counter and threw it at Aunt Magda. Thankfully her aim wasn't very good. The blade flew by the woman's head and skewered a self-portrait of my grandfather's. Refusing the offer of a drink to calm her nerves, Aunt Magda excused herself and left in tears. My father, although not exactly Aunt Magda's biggest fan (he once caught me playing with a compact she'd gifted me, and wasn't very amused), encouraged the lady to visit again, assuring her they would hide any sharp objects. But she never did return.

I remember vividly the last time I saw my grandmother. "Go on, Michaś, say hello to your babcia," Dad nudged me toward the hospital bed where lay a mummy, her skin papyrus-thin, her cheeks sunken, more bone than flesh. Just like her speech, my grandmother was twisted and contracted beyond recognition: her eyes were hyphens, her lips an ellipsis, her spine a question mark. I watched her like one mused over hieroglyphs. I knew she was supposed to mean something, the harsh memory of that ancient meaning sticking like dust to my throat. But try as I would, I couldn't make any sense of her.

"Hi, Grannie," I said. If the body moved, I didn't notice. The skull that turned toward me did it so slowly that none of the countless tubes and wires keeping my grandmother moored to this Earth stirred. There was no light in the eyes staring at me, the same eyes I had witnessed all those years ago, the day she truly died, or should have, perhaps. Her hand raised an inch, and her lips quivered, and for a moment I thought she might say something in that alien language of hers. But no words, not even gibberish, emerged from the toothless mouth. Although the heart monitor next to the bed insisted otherwise, there was no real life there.

She died a month later. The procession to the grave site was tense, even for a funeral, on account of the presence of Aunt Gabriela. As a matter of protocol, she and her husband were walking beside my parents, but no words were spoken. Eyes fixed on the coffin carried before us, our feuding families marched ahead in silence.

After my grandmother was laid to rest and the mourners began to disperse, a woman in black veil and matching gloves approached my father and shook his hand. "I'm sorry I'm late, the traffic... My condolences, Jacuś." It was only as she swept aside the veil that I realized it was Aunt Magda. She looked much older.

"That's quite alright. Thank you for coming, Madziu," Dad said, squeezing the woman's hand. "We're going to our house for some drinks now," he cast his sister a grave look. "You should join us."

"It's very kind but I think..." Her eyes wandered toward the grave. "It's just..." She covered her mouth and stifled a gasp. "It's too hard. Once again, my sincere condolences." She shook my father's hand and rushed off, disappearing among the crowds.

It only took one round of vintage whiskies for the fragile armistice between my father and his sister to collapse. A fierce battle ensued, insults ricocheting against the walls. "Michaś, why don't you go play?" my mother said, nudging me away from the bickering adults. I didn't have to be asked twice.

I ran into my grandmother's pink palace. As I closed both doors, it occurred to me I would never have English lessons with her again, never again be forced to recite the irregular verbs—a thought once welcome, but that now made me feel hollow inside. I wasn't yet a literature lover—that came later—but I guess I wanted to feel close to her because I opened the bookcase and let my finger slide along the books' spines, their skin worn and fragile like the hand I touched that day in the hospital. I stopped on D. H. Lawrence's The Rainbow, thinking the title sounded cheerful and magical. To my surprise, when I opened the tome, I found the front page of a different book: The Master and Margarita. I started reading the novella, an obscure anti-Soviet story set in Moscow, involving Satan and a talking cat. Impatient, I began paging through the volume when, on page 24, something stopped my progress. A bookmark, I thought, but it turned out to be a sepia photo depicting a beautiful woman spread across a couch, one of those long cigarette holders in her hand, winking at the camera. She was stark naked. The woman looked vaguely familiar. I turned the photo around. A written inscription said in English, "We'll always have Beirut. With love and affection, your Madzia." As I lifted the book, more papers slipped out. Getting down on the floor, I browsed through the findings. There were photos of Aunt Magda in various states of undress, one of her and my grandmother seated on a terrace with a hookah, the latter blowing smoke rings to Aunt Magda's beaming delight. Behind them stretched a dusty palm-lined road.

I sensed I had made some discovery, but I wasn't sure what it was, exactly. My grandmother had taught me many words, but none to describe the friendship I witnessed, a friendship that turned out to be so much more than any of us had ever suspected. It was then I realized I'd never really known the woman. She was like one of the puzzles we used to assemble over many a winter evening, the few remaining pieces of which lay now scattered before me. Smiling, I touched the faces of Aunt Magda and my grandmother, who seemed to smile back at me from a distant time and place. Then I collected the findings and returned them back to The Master and Margarita and replaced it in the bookcase, where it remains even now, hidden behind my father's neglected whiskies. I never told anyone about the discovery. It would be something only my grandmother and I had. Our little secret.

As I write these words, I find myself in a studio apartment in Dagenham, London. It's a dump, but we've made it our dump, Manny and I. Across the street there is a little Buddhist center—nothing grand, just a decrepit house with a Buddhist flag. I can hear chanting coming from within: Om mani padme hum, om mani padme hum, om mani padme hum. We used to loath those morning prayers, but I've taken a liking to them. The repetitive chants remind me of the countless times I was made to repeat the irregular verbs. That was also a kind of prayer, even if I didn't know it then.

I hear the bathroom door open. Approaching me from behind, Manny says "Morning" and kisses me on the back of my neck. He smells like soap and coconut oil.

"Morning yourself," I squeeze his hand. "They are singing about you again," I point my chin toward the Buddhist temple. "Did you know your name means 'jewel' in Sanskrit?"

"I've been called worse. You busy?" he says, laying his wet chin on my shoulder

"Almost finished. Blazing hot today. What should we do?"

"We could go to Regent's Park, have ourselves a little picnic?"

"Sounds like a plan. Why don't you dress while I finish this paragraph?"

"Okay, but make it fast."

You heard him, folks, I must cut this short story short.

I never knew my grandmother. Not truly. Like A Passage to India, I never bothered to read her. Now, I can peruse Forster anytime I want, but I can never go back to her, flip through her pages, scour the footnotes. Oh, I know the gist. But she'll always be just that: a synopsis. Such a terrible word, isn't it? Like a disease. I was never brought up to be a religious man, but I know the devil is in the details. Well, she took those to the grave, leaving only hints and clues. But sometimes secrets are more powerful than the truth. In bequeathing me this mystery, my grandmother became my unlikely muse. Her secrets lingered with me throughout the years. I speculated about her exotic life in Beirut, her torrid affairs, the Bohemian artists whose paintings adorned her bedroom, the life she abandoned in London, the sacrifices she had made. Before I knew it, I had constructed in my mind a work of fiction with at its core a grain of truth. It would be years before I penned my first story, but she was the spark, and the language she gave me—the language which allowed me to escape a country and a culture I found increasingly oppressive—that language was the fuel. She attended my birth, and in her death, delivered me into a brave new world. No, not just one. An infinity of worlds, both real and imagined, available right at my fingertips. It was she who handed me the key to that universe, and in doing so, set me free.