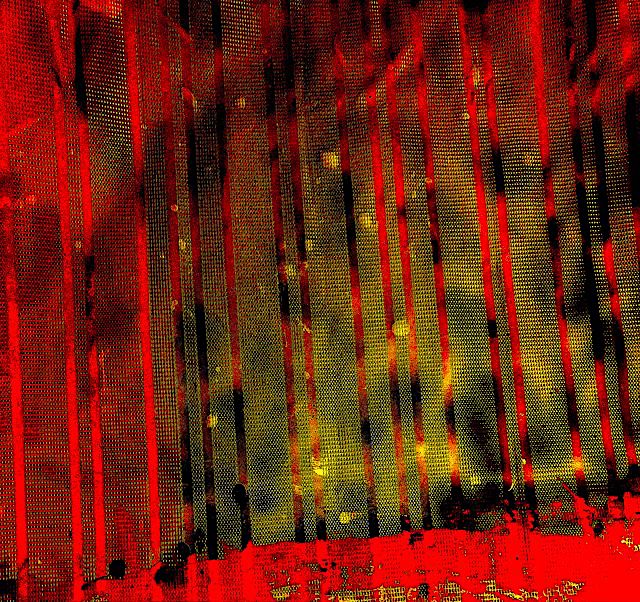

Photographic artwork by Kris Saknussemm

When Janie's family moved away, I was bereft. For years, our mothers hung our washing on a shared clothesline, and sometimes, if they weren't paying attention, we ended up with each other's wool sweaters or stockings. While our mothers pulled dandelions or did whatever chores they did, we dug in the dirt and ran around playing chase and used scissors to cut leaves into new shapes. The scissors were precious, one pair between us. One time, when our mothers weren't looking, we cut our hands with the scissors, not deep. We pressed our palms together so the blood mixed, and we became blood sisters. That was when we were quite small. She said she would write from the new town, but she never has.

Cripple Creek is not a big place. Our mothers would have known each other even if we hadn't been next-door neighbors. They probably would have been friends no matter what. And maybe they would have stopped being friends no matter what, too. My brother says they fought about money, something with money, but that doesn't seem likely to me. My dad thinks it was to do with some boy from their past. No one cares that much what they fought about, though.

When I say fight, I mean fight, not argued or had a spat. They had a physical actual fight in the yard, and I was home and heard some of it, but when I looked out the window, the clothes on the line made it hard to see exactly what was going on. They were yelling, almost like growling, and there was a hard smack, and that was my mom hitting Janie's mom in the face. Really bad. I remember a sound after that, too—a kind of moan, like when a cow is calving. I'm not sure which of them made that sound.

There was a washbasin full of soapy water out there, for the washing, and another basin for rinsing. The water they squeezed out of wet clothes before they went on the line went directly into the earth, for the garden. Cripple Creek is really dry. You can't waste water. After the smack, Janie's mother yanked a sheet off the line and pressed it to her nose to staunch the blood, looking at my mom with shock and hatred (yes, I would say hatred). It was our sheet, not hers, ruined. She threw it into the soapy washbasin and went into her own house, and not many days after that, the whole family moved away. Janie only told me they were leaving on the morning they left. She acted like it was no big deal, like we weren't even friends.

Later a rumor started up that Janie's mother's blood wasn't red. The first color I heard was black, but my brother heard green or blue, and Philip up the street said he saw Janie's mother right after and the blood was yellow, sickly. I don't see how Philip could've seen anything, though. He's a liar. And anyway how could blood be any color other than red? That's what I told the teachers when they asked me, and the sheriff, too. "People around here are crazy. They'll say anything to get attention," I told him.

I remember dumping out the washbasin, though. I remember the sudsy water sinking into the earth along with the clean, and I remember using the ruined sheet to wipe away the green ring left in the basin. Or I think I remember it. It was a long time ago now. People don't talk about it anymore. It's like Janie never lived here. My brother left for college in Colorado Springs, and my mother made friends with the mother of the new family that moved into Janie's old house. The kids there now are just babies. Useless.

Probably the blood that mixed with mine that day with Janie was red. I don't trust my memory. It was only a little cut, and I bandaged it up right after. She bandaged hers, too. We used scraps from the scrap-bag, and they were dark, so the blood could have been any color. You can choose what color it was, and we'll count out the letters. That's how we choose who's It now, in games at the playground at school. There's a rhyme, and if we point at you, you say the name of a color. When it's my turn, I always say red. It's none of anybody's business what color it really was.

Note:

A counting-out rhyme beginning "My mother, your mother, lives across the way" is cited in Henry Carrington Bolton's The Counting-Out Rhymes of Children, 1888. Emelyn E. Gardner's "Some Counting Out Rhymes in Michigan" in The Journal of American Folk-Lore, October-December 1918 (Volume 31, No.122) contains several versions of the rhyme, including some very similar, though not identical, to the one that was popular in the 1970s in Rochester, New York: "My mother and your mother were out hanging clothes. / My mother punched your mother right in the nose. / What color was the blood? / R-E-D [or B-L-U-E or whatever color is named] and you are not It." Repeat the rhyme until one person is It.