The doctor tells me the only way I could have avoided this condition was if I had managed to lose 200 pounds in under two years. Her hands are both palm-up, and she appears to be shrugging slightly, but beneath her blue mask, I sense a frown. Her small eyes don't seem sorry or amused, just resigned. Another day, another fatty.

I have trouble processing sounds when I'm upset. All I can hear is my blood whooshing in my ears like the ocean, and I feel a little dizzy. I always feel pukish at doctor's appointments. I ask this woman I just met but to whose care I am entrusted to please repeat herself in case she misspoke or I misunderstood.

The doctor says again, a little louder and a little slower, as if my fat cells have reached my brain, "Yes, we'll do the test just to make sure, but there's no doubt about it." My condition has returned because I didn't lose 200 pounds. Her voice is abrasive and has that know-it-all tone. Granted, I do hope she knows it all when it comes to medicine, but her timbre feels like she always speaks this way, braying and in charge.

I say, "Oh, okay, let's do the test though, just in case." I tend to go along with what doctors tell me. Because then I'll just be fat, instead of fat and difficult, although the former necessitates the latter.

I know full-well that at that time, I am 222 pounds in heavy boots. I know this because the much-nicer nurse had weighed me moments ago, and instead of closing my eyes like I usually do, I watched the numbers go up and up.

What I don't know is if the doctor knows my weight or not. She holds the clear plastic clipboard with my information, but I don't think she had time to read it. She took one look at me and said, Well, this person should've lost 200 pounds. And, for a moment, I wish I had.

I wrote "at that time" deliberately. You don't yet know when that story takes place. The verbs are present tense, but that doesn't mean anything. I may weigh a good deal more now. I may weigh a good deal less. Or, maybe, I weigh precisely the same.

Why would you want to know that information? To judge how much I'm worth?

In my work on trauma survival, a refrain I often use is The only good victim is a corpse. It's meant to provoke. Obviously, I don't wish survivors or myself to be dead. It's the idea that a rape survivor never does anything "the right way" in the eyes of the patriarchy. Should have reported it earlier. Should have not reported it. Should have turned into a saint. Should have been pretty. Okay, not that pretty. Should have kept quiet. Should have been louder, sooner. Should have fought harder. Should have laid back and enjoyed it. Since we can only do so many direct opposites at the same time, I concluded, the only way we could have been raped the "right way" was if we just, well, died afterward, instead of having been such a blundering bother.

I tried applying that same, twisty rhetoric again to myself, this time not as a survivor but as a Fat Woman. The only good Fat Woman is a corpse. Closed coffin, of course. Even after there is no life left, no one wants to see that.

I remembered something I hadn't in a long time: an eighth-grade field trip for life sciences. We were going to the cadaver lab! As an adult, writing this, I am not sure how appropriate it is to take 13-year-old, sheltered, prep-school children to see literal human cadavers. But at the time, I didn't think anything of it. My older sister had gone two years before, and that's just what you did in eighth grade. I was even excited. Everyone already thought I was a freak, so I figured I might as well play up the goth angle if I could.

When we arrived at the basement, we were greeted with the smell of formaldehyde, nauseating and frogfull. On two tables lay two corpses. It was better to think of them as not-human, as never been human, just tools for science. The morgue worker who was acting as tour-guide to us junior high students explained this was ethically fine, because the donors had signed over their bodies to be used for scientific, educational purposes. One was a man and the other a woman.

I remember they still had their hair. The man was blondish and balding prematurely. The woman had long, straight, black hair, oily and lank.

Both the man and the woman were sliced up at their abdomens, dissection t-pins holding back various flaps and chunks. Their organs were dyed different colors and labeled. One by one, all 60 of us paraded past and took a gander. Liver, stomach, large intestine, small intestine.

There wasn't much of a difference between the male and female internally except the woman was overweight and the man wasn't. When we peered into her body, we could see blobs of yellow fat nestled around various organs. We could see her body as worse.

Us girls whispered to each other, Ew, let's never, ever get fat.

Our teacher pointed out the dead woman's fatness as well. Look at how her organs are squeezed. Look how hard her heart would've had to work.

I asked what she actually died of, though, even though it wasn't time for questions. And the tour-guide said he didn't know.

Then the peewee quarterback fainted when it was his turn to walk past the table, and he brought our tour to a halt. Someone had brought coffee grounds for him to sniff, and we all said, Don't worry, Jesse, don't be embarrassed. It happens to the people you'd least expect.

I despised my teacher. She thought I was a freak, too, and a very dim one. But looking back at that day, I can't help but have a small twinge of compassion for her. She was a large woman, too. But I guess she still thought she had time because she wasn't a corpse.

The only good Fat Woman is not a corpse. Because even in death, your body is something to be ridiculed, judged, mocked, and deemed especially disgusting. There was never a good Fat Woman. The very idea is a joke. Because our bodies are a joke.

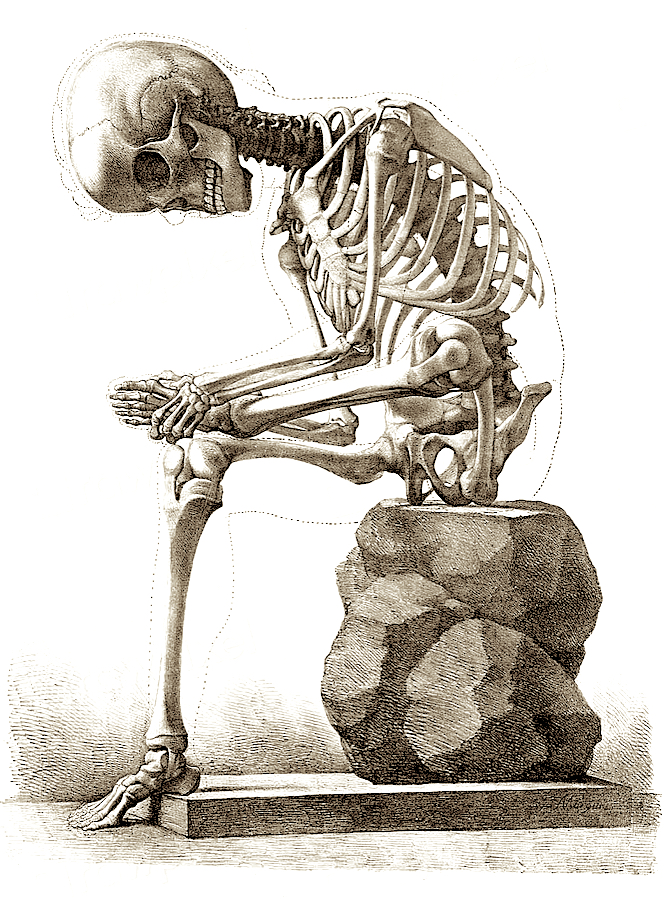

The average human skeleton weighs about 22 pounds.

The doctor who was—unkind? strange? confusing?—to me is my gynecologist. I am her patient because I found myself seven weeks pregnant with my second child and with no doctor. We had moved across the country, so I couldn't use the same gynecologist I did with my first. That doctor? She was fantastic, laughed at my jokes, and was more careful with her words. My children will be two years and one month apart when the second one is born. From September 2021 until July 2024, there were only three months in which I wasn't pregnant or breastfeeding. Some people lose weight when breastfeeding, but I gained and gained. My weight of 222, I was counting as a win.

I am not arguing I was a healthy weight to get pregnant. I am not arguing I was secretly beautiful and sexy and you are just too stupid and narrow-minded to see it. What I am arguing is it is particularly disheartening to hear your medical professional say, Ew, no, lose two hundred pounds please, when you know—hope—that over the next seven months or so you are going to get so much bigger. You are going to gain approximately 25 to 35 more pounds. And if you are a whale now, then surely by the end of this ordeal you will be the size of a zeppelin, and that's if things go well.

If you were to lose 200 pounds, you would, of course, die, but so would your child, your miracle, the life you are bringing into this world. Are they supposed to die, too? For what? To avoid a dangerous but completely manageable condition? To avoid the shame of having a Fat Woman for a mother?

According to a January 31, 2024, Washington Post article:

Many nurses admit: They feel repulsed by our bodies and do not want to touch us. Doctors are more likely to view us as a waste of their time and have less desire to help us. We are hence, unsurprisingly, far more likely to die with serious health conditions that have gone undiagnosed."

And that's just the first paragraph.

The author, Kate Manne, a professor of philosophy at Cornell and author of Unshrinking: How to Face Fatphobia, continues:

Many fat people recall going to the doctor with symptoms unrelated to their size yet being summarily told to lose weight, when a thin patient with the same symptoms would receive treatment and medication. In addition to facing misdiagnosis, or no diagnosis whatsoever, larger people are often mistreated during the medical encounter. One study showed that fat patients were rated more negatively by doctors on 12 out of 13 indexes, including "this patient would feel like a waste of my time" and "this patient would annoy me."

Doctors want us dead. For them, perhaps, the only good fat patient is a dead one, one they don't have to pretend not to be disgusted by.

My condition isn't hard to guess. It doesn't take a genius, especially if you have been pregnant. But I don't feel like telling you. Why is it important for you to know? So you can decide what I'm worth?

I've noticed I've included a lot of rhetorical questions, which is not my typical style. They weigh a lot, too.

I've always been considered fat. But the thing is, I wasn't. This part is tricky. I don't want to come across as, Well, unlike you dumb hos, I'm not actually fat, or I wasn't always fat. That's not my point. Unless my fatphobia is that deep, that ingrained, that I am always distancing myself from "actual" fat people, because the worth and size are so intertwined for me. And I need you to believe that I am worthy, at least worthy enough to read this essay. Look, I spent a lot of time writing it.

In high school, I weighed 120 pounds. An important element here is that I was 5' 10". And still, somehow, fat.

Senior year, we get measured for our costumes for drama class. The popular, pretty girl who looks like Blake Lively and I need the same type of pants for Richard III. We measure each other. Our waists are the same: 29". But somehow, my body is wrong. I know this, she knows this. And I don't know why.

The pants are wool or, fake wool, more likely. They make my ass look like a diaper or a half-deflated balloon. Blake Lively, though, she looks amazing.

I don't know how, exactly, I went from "fake fat" to actual fat. When I was a child, in high-school, and college, I wasn't fat, medically nor aesthetically. I think there's a few reasons I got that label.

For one thing, I was born in 1990. A little too-young to bear the worst of heroin-chic and the even more outrageous beauty standards of the time. But it was still in the air. Skinny, boney, unwell. Paper-thin, paper-thing, girls. And with my early-puberty double-d's, ample butt and thighs, no matter what, I was never going to be that.

In the 90's, we had catch-phrases like "Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels." We had the idea that if you're hungry, you're actually thirsty, so no more snacking. We had Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen as our ideals. In the 90's, the fattest, grossest you could ever look like was Hillary Duff or Kate Winslet.

Emma Loffhagen writes for Yahoo Finance:

This mosaic of toxicity was inescapable. There was an unspoken understanding among women that we were on a collective and never-ending diet. It was a hellish time, but it seemed completely normal."

We hated our bodies because we had to.

For me, the culture at small was also fucked. Namely, I was part of a charismatic Christian community. The link between Biblical notions of marriage and thinness seems intrinsic to me. If the body is bad, then having more body is worse. If women are responsible for the lustful thoughts of men, women should have shapes that are hide-able. If being a good woman was being meek, subservient, quiet... having a smaller body, the better. And even better if that body is child-like, the way a woman should be.

When researching this piece, I found stirring, personal accounts about fatphobia in Christian circles, such as Ashley O'Mara's for America Magazine. But what came up the most when I Googled Christian Fatphobia were Christian forums and blogs about how being fat is a sin. The pieces are titled things like "Is It Okay for Fat Christians to Exist?" The authors do not hesitate to cast the first stone. The Transformed Wife is one of many, many examples. Her blog posts are mostly about being a Biblical wife and about how to lose weight. This is not a coincidence.

I think I was a deemed fat before I actually was because it was sort of a shorthand for unacceptable. Fat is, after all, the same thing as undesirable, strange, other, sinful, wrong. I am, and always have been, terribly awkward as a person. Why speculate about someone's abusive situation at home or possibly undiagnosed autism when you could just call them fat? Cruel people always sense insecurities and would have found something no matter what—fat was just the easiest way in.

But the funny part was, I was desired. This is not a pitiful account of malignant loneliness. While it is true that in high school, I couldn't get a date, I also graduated in a class of 60, 15 of whom were male. I have dated my entire adult life. I've had crushes on me I've requited, crushes I haven't. I've had crushes on people who didn't feel the same way about me, crushes on people who did. In other words, the wide range of libido experiences one would expect, but not of the fat friend you see in the movies. It wasn't that I was rejected romantically for my weight in a way that formed and hurt me; it was that people assumed I was.

If you took a look at me and decided I was unattractive and fat, then you would be repulsed and surprised to find out not everyone felt that way. In fact, a good number of people did not.

Once a fellow writer whom I never met in person called me about a publisher with whom we had both had run-ins in the past. She told me she understood I had issues with this male publisher and wondered if I could lend an ear. She had tried dating this man, but then things turned shitty and confusing and bad, if not downright abusive. She was asking me to navigate the situation because I had dealt with the publisher (professionally, not romantically) before. Of course, I was sympathetic and tried to help her navigate the world of unstable, artistic men as best I could. I tried to validate her feelings and tell her to block him and never look back. She ended the conversation by wailing, "You don't know what it's like to be cute, thin, and blond and have men throwing themselves at you and then get confused when they find out what a weird personality you have or that you're neurodiverse."

I said, "Um." And I never spoke to her again.

Because the moment I started to say I can't turn every head in a room but I can still turn some, the moment I start to become defensive and tell her men have always flirted with me, wherever I go—gas stations, poetry readings, bars, libraries, friends, friends of friends—then I look stupid. Like I'm making up lies to try and one-up this woman who just told me a saga of emotional abuse. If I were a good person, I would have let it go immediately. If I were a bad person, I would have laid into her. But because I'm a medium person, I went with "Um."

She thought it was okay to tell me that we couldn't possibly have the same experience with men lusting after us, based on my Facebook selfies.

Then, of course, I did actually become fat, medically and aesthetically. It happened sometime in my late 20's. There's something disheartening about being called fat before you were. There's always that fear—what if the people who called me fat back then could see me now? Would they say, My god, she's even worse now? Were they fortune tellers, who weren't calling 120 pound me fat, but 236 pound me fat? Because they knew? Because they knew, in the end, they would always be right? But the line of blame, of causation, of "Cruel people called me fat when I was healthy, so I became fat," doesn't hold water. There are ethical concerns of eluding self-responsibility. Moreover, it just doesn't seem terribly robust. People also told me I was selfish, bad, a terrible student, and a slut, and I don't think I became any of those things.

If I had to choose reasons why I became fat, for real, even before I had children, it would be something like a combination of a sedentary office job—which I hated—overeating due to stress, age, years of birth-control, mild substance abuse (nicotine), and mental health. Genetics may have played a role. I don't want to blame the world around me or the way I was treated. I don't want to be that fat woman. I made choices. They added up to an unhealthy weight. And there you have it—fat now, but also funnier, more confident, kinder, wiser, less selfish, and less judgmental. In other words, I got older. In other words, I grew.

And yet, I can't help but think there may be something to the notion that being told your body is garbage, isn't good enough, isn't up to snuff, may have had some influence on treating my own body like it were garbage. What if I were told my body is worth caring for? What if my body were never a punchline?

Sometimes the best way to acknowledge one's privilege is to, well, acknowledge one's privilege. In an essay about fatphobia, it seems a disservice to not mention that fatphobia disproportionately affects people of color. The very origins of fatphobia stem from, in part, prejudice against Black bodies.

Much work has been done by sociologist Sabrina Strings in her book Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia. Hannah Carlan for the Barbara Streisand Center writes in a book review:

By the early twentieth century, the culturally, scientifically, and religiously embedded derision of fat as a sign of racial Otherness, intellectual inferiority, and moral debasement set the stage for a century that culminated in the newest moral panic around fat. The so-called "obesity epidemic" which problematizes Black women in particular as "social dead weight" (Strings 2015), relies on deeply political knowledge about bodies cloaked in rhetoric of objective science.

Carlan continues:

With the rise of the so-called "obesity epidemic," Black women's bodies continue to be subject to medicalized disgust despite the significant evidence that weight stigma, not weight itself, constitutes a serious health risk and predictor of negative health outcomes. The stakes of this debate around "obesity" are thus exponentially higher for Black women, but debates around medical racism rarely address fatphobia. As such, this text [Strings' book] constitutes a much-heralded contribution to our understanding of the relationship between white supremacy and thin supremacy.

I am white. I wrote this essay from a white perspective, having had white experiences in a white body. I do not wish to speak over or for BIPOC. All I can speak for is myself and what happened to me. But I want to, need to, acknowledge that whiteness has kept me relatively safe. Hell, it may have even kept me alive.

In a private mom's group, I open up about my diagnosis. I am vulnerable and raw. Three women rush in and tell me they know a teeny, tiny woman with the same diagnosis. Or that the condition has more to do with placenta. One woman tells me how it's genetic, and skinny women get it all the time.

I want to acknowledge they are all being kind and trying to make me feel better. But they've all said the wrong things. I am not teeny tiny. People don't feign surprise when they learn of my diagnosis. What I comment is, "I hear what y'all are saying. I mostly agree, and I appreciate you. Where I'm at emotionally is that even if I 100 percent caused this, which I didn't, weight is merely a risk factor, not cause, but even if we say it's my fault for being fat, I still deserve dignity and care. Even if this is my fault and caused by my fatness, I don't deserve to have stigma around my condition because most of America is fat with poor diets. I don't deserve stigma because my weight has no impact on my worth as a person or capacity as a parent. The attitude should be, Okie dokie, let's figure out how to best care for the fetus. Not judgment. Ya know? So I don't want people to know I got a thing associated (fairly or not) with fatness, because that automatically turns into a once-over. Maybe you think I'm fat. Maybe you don't. Okay."

I think the other moms and I in my anecdotes have the same aim: distancing ourselves from "true" fatness. Yes, I might be overweight now, but it's a temporary embarrassment, like how paupers are temporarily inconvenienced millionaires. Or, I might be "medically" overweight, but I'm still hot. I'm still hot, right?

I'm not arguing from a medical perspective or from a health perspective, but merely societally. I am subjectively fat. My boobs, thighs, and butt have always been huge. My waist isn't thin, but it's there. And that's fine. It doesn't make me better or worse than people smaller or larger than I am. It just makes the space I occupy uncomfortable and hard to navigate. You might say obese in a medical context, or average if you see me in a supermarket.

Sometimes, I would get a crush and think "What if he finds me fat? What if I'm not thin enough for him?" And so on. Dating a douchebag for four years will do that. It's not, "Does he like fat women?" it's, "Does he consider me fat?"

That ex? He thought I was so fat and disgusting, but he continued to date me, when he, you know, could have just dated a skinny woman. He thought I was fat and disgusting, but every man who spoke with me was flirting outrageously with me. Now I know the word I was looking for is insecure.

In 2018, I have an ovarian cyst burst. Looking for answers, my doctor posits I may have PCOS. By the time I have my miscarriage in 2020, this diagnosis is confirmed. It's a pretty common condition. Basically, what it means is instead of fat cells just going to my belly or butt, they also invade my ovaries and make my periods excruciating. It also makes it harder for me to lose weight.

In some photos, I look chubby. In others, I don't. Often, the photos were taken the same day.

Some snapshots.

It is the early two thousands. My father is driving me and my younger, skinny sister home from high school. I am about to graduate, but, another story in itself, I am not allowed to drive the family van. (Basically, I had a "B-" GPA and thus was deemed unfit to drive.) My father and I are chatting about me getting a summer job after I graduate. I joke that maybe I will have to get a job at Wal-Mart. Because what we did as a comfortably middle-class family was punch down. And what could be lower than having to work at Wal-Mart? My father said, matter-of- factly, "Working at Wal-Mart makes you fat. You're fat enough already."

What does that mean? How? Why did he say that?

We drove the rest of the 20-minute commute home. I hated my hips for filling my uniform, pleated skirt that literally no one, not even Blake Lively, looks all that good in.

Ironically, between Sophomore and Junior years of college, I do end up working a summer at Wal-Mart. I couldn't secure a "better" job because I had spent the previous spring semester abroad, and it was hard to apply or look into jobs when you're in a different country. So at the end of the semester, I came home with no prospects or ideas.

I worked three, long, hard months at Wal-Mart. Specifically, remodeling. The dirt never left my arms. I remember looking at them, bored, at church. I got in the best shape of my life, and the muscles never looked more defined under that dirt.

I am ten years old and eating dinner in a restaurant in northern Arizona. We are on vacation. Most likely this restaurant stop was on the way to a five-day camping trip with our Christian cult. I am ten and don't know anything, including what's happening to my body. I am hungry all the time. My chest hurts, and I am at a c-cup. No bra, because the cult had decided I am too young.

I order something that comes with sweet potatoes. A healthy choice, I think to myself. It comes with cinnamon butter, a luxury we had never experienced at home. I asked my parents what it is, and my father says not to eat any more of it because it will stick to my hips. I am confused because it's oily, not sticky. He clarifies it'll make me fat, and then my hips will be too big.

I am 17 years old. I am on a summer trip in Austria with my high-school class. The teacher in charge of this overseas adventure stops me at breakfast and says, "Back in my country, we would have called you sturdy as an ox. A sturdy, indelicate girl, but a good worker."

"Oh," I said, and I ate the red pepper I picked out from the salad bar for breakfast.

I am 23 months old. This is my first memory, so it's most likely a memory of a memory of a memory. My older sister, thin, 38 months, my father, fat, and I are visiting my younger sister, scrawny, and my mother, likely anorexic, in the hospital. My younger sister has just been born. Small, red, crying. And we are there to see her. It's the middle of the night, I believe my older sister and I are in pajamas. My mother is eating hospital Jell-o. I ask if I can have some. And my mother and father exchange a look that says, Little piggy, always wants food. And then they say that, with their mouths. Always hungry, always wanting food.

This is my first memory of being alive. Being told my wants are a joke. Being told my body is an apt subject of ridicule.

Why the fuck did a grown man think it was okay to make that comment—any comment—on my 17-year-old body? At the time, I wasn't angry with him. I felt he was trying to, in his own way, give me a compliment. You might be fat, but your body wouldn't be considered worthless, at least where I come from.

The person I was angry with, actually, was my father. He and this teacher were friends. Both were Speech and Debate coaches, which is how I ended up on this summer overseas trip. I felt most teenage girls would be able to tell their parents an adult said something about their bodies that made them uncomfortable or struck them as strange. I knew, even then, I had no such recourse. Not even my mother, because she was a good Christian and deferred to my father in all things.

I am four weeks pregnant. Or, I was, and then I wasn't. This is two years before I conceive my first child, the one that stays, and four years before my second. I came in for an ultrasound, and then the doctor inserted the machine into my vagina and still couldn't find anything. It feels cold and awful, and my insides are so empty. I joke that this is how I got into this mess in the first place. The technician doesn't laugh. She says to come back in a few weeks. A few days later, I get my period, so I call and explain I don't think I need to come back. They say I do because they need to talk about my weight.

This is obviously the most important, pressing issue. At the time, I am at my absolute heaviest. 236. I don't feel like this is the most interesting thing, medically speaking, about me. But I go to the second appointment anyways, and the small, southeast Asian doctor tells me I am pre-diabetic. I don't know any better, but now, I would have demanded they run some tests. Any test. She just decided, by looking at me. I nod and nod. I pet my belly as if there's still someone there. I cry and say, "What do I do?" And she says, Lose some weight.

Ah, right, I will add that to my to-do list: Mourn my miscarriage privately and quickly, put more gas in my car, lose some weight. Got it.

When I weigh my heaviest, I publish my first five books of poetry and two books of illustrations. When I weigh my heaviest, I get married. I look beautiful at my wedding.

Again, I am not arguing that, medically speaking, I was fine. I am not arguing that, outside of smiles and a pretty, off-white dress, I was at all attractive. Yes, I should have lost weight. I shouldn't have gained that extra 16 pounds. But the thing is, if I lost that 16, and then some, then a lot, so that I was medically and aesthetically trim, that, not marrying the love of my life, not the seven books, that would have been regarded as my biggest achievement.

Just ask Adele.

When I am at the gynecologist after my miscarriage, she doesn't ask how I'm doing. She asks what I'm doing to lose weight.

I say, "Hold on, I have questions. Why do I have so much excess vaginal fluid? Why does it hurt when I masturbate to orgasm?"

She looks appalled that I experience sexual pleasure. She looks truly disgusted that I would have questions about my body. This was in February of 2020, so no one is wearing a mask yet. Her little mouth pinches down in the corners. And she says, "I don't know. Were you doing anything different?"

And I say, "No, just digitally trying to have a pleasant time with myself." I say it lightly, almost a joke. (We all know someone agreeing to have sex with me, even myself, is a joke.) I think about specifying I did this before I knew I lost the baby, not after, but then I don't know if that would make it better or worse.

The doctor says, "Hm, I don't know why either of those things are happening."

I learn later that both excess vaginal discharge and cramping after orgasms are common pregnancy symptoms, especially during the first trimester. Because I was pregnant. But then I wasn't. And that's the important medical fact here.

I wish I told that doctor that no fat woman has had sex, actually. It's too repulsive. And if by some miracle, they get pregnant, that fetus always dies, because no fat woman has ever given birth.

According to a paper published by BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth in 2020:

Nearly 1 in 5 women reported experiencing weight stigma in healthcare settings. Percentages differed by BMI, with 28.4% of participants with pre-pregnancy obesity endorsing healthcare providers as a source of weight stigma. Experiences occurred between "less than once a month" and "a few times a month." Obstetricians were the most commonly-reported source (33.8%), followed by nurses (11.3%). Participants reported feeling judged, shamed, and guilty because of their weight during healthcare visits.

That doctor was fired a month or two later. I don't know that for sure, but I assume based on the wording of an email I get. Normally, when a doctor leaves a practice, the email is something like, "We wish her the best of luck," or even "If patients wish to stay with Dr. X, she is now working at Y clinic." But there's nothing like that in this email. Just, "Dr. X is no longer with us."

She has an unusual name, so I find her on Facebook easily. In her profile picture, she is smiling with her husband and toddler. They stand, fitly, atop a mountain. They conquered it. They conquered the shit out of that mountain in their Lululemon's. They look so hydrated. No one has hydrated as well as this family.

No doctor has ever criticized my smoking. When I smoked, before my pregnancy that stuck in 2021, I would always tell doctors I smoked about seven cigarettes a day. And they would make no comment.

In 2013, no one believed how much I was working out: 45 minutes of cardio on an elliptical machine, 45 minutes of yoga, five to seven days a week.

In 2020, well into the pandemic, I would bike up and down mountains. I loved how much it hurt and how free I felt.

When I was my heaviest, I wore a size 12. At my thinnest, a size 10. Not a lot of variation between. According to a Forbes article, in 2016, the average American woman is between a size 16 and a size 18. It also tells me that a size 10 has a 28" waist, which I never had. Articles ranging from 2016-2023 from Today, Diply, Racked, The Cut, Taylor & Francis Online, and World Population Review all support these claims. Most cite a study done in 2016—which is significant for two reasons: In 2016, I was thinner than 222 pounds. And, even by what we knew then, I was fat, bullied, unacceptable. And I cannot imagine the average dress size went down in 2020, which is when I was first shamed by a gynecologist.

My size compared to the national average doesn't mean I'm thinner and better than the average American woman. This does not mean I am healthier. This does not mean much of anything.

Except.

There is something enormously frustrating about being told I am fat, other, disgusting, bad, when all I did was have the audacity to be pretty much an average size. (As stated earlier, I am 5' 10", but I think we can all agree that that can't be helped.) Why am I being othered by grown men, by my father, by classmates, by doctors, by coworkers? What makes me other, when I'm smaller than the average American woman?

I suspect this all has to do with notions of women taking up space (they shouldn't) and who can be seen in public (only beautiful, thin people). It has to do with which perceptions dictate the truth, which opinions matter. Not mine, not women's, just men, the men, the men's, the grown men, who notice me existing, and immediately wish I was less.

This is not a body-positive essay. For one thing, I'm getting it as an ass-tattoo, in case you missed the implication in the title. For another, body-positivity doesn't feel genuine to who I am as a person. I am in no way knocking it for other people. If it works for you, it works for you. I am also not convinced I don't need to lose weight. I do. I would feel better a few pounds lighter. It would put me at less risk for serious conditions such as diabetes and heart disease. It is reasonable to say I carry extra weight. I also don't buy it's just genetics. I believe genetics can be a factor, but I also could be making better choices in what I eat and how often I move my body.

Here is where I'm at. Your opinion of my body is not important. It is not my responsibility. I do care because I'm human and want everyone to think I am hot shit, but at the end of the day, it's just not that interesting. You think I'm ugly, mid, could make myself look better. Okay. You happen to be attracted to me. Okay. That's fine. It's not interesting. Your opinion about my body isn't enough to change it. (If body-shaming worked, we'd have far fewer fat people.)

You think I'm fat. You think I take up too much space. Okay. That's not an interesting fact or topic of conversation. Where are we supposed to go from there? Do we have to keep dwelling on it? Why is your opinion of my body interesting, important, valid, worthy, the sole dictator of reality? Is your ego really that large that you think I should be shook?

Some days, I still hate my body. Alright, a lot of days. But if you hate my body too, why is that at all interesting or important? I don't want to write over my blobs of fat, "Beautiful I am beautiful I am beautiful," because I feel like if you have to make the argument to yourself or other people, then it feels silly. It feels silly to try to convince anyone I am aesthetically pleasing. I don't feel like arguing, "Hey, I'm secretly hot, you just can't notice right away," or, "Well, actually Adele was hot all along," or, "I have some nice features." I just don't think aesthetics are something you can argue your way into. I don't think I can change the parameters on what is currently acceptable aesthetically to you personally or to the culture at large.

I also don't think of any of my friends as ugly. Maybe that's enough.

Where I find myself landing is a sort of body-neutrality, with an eye towards the gross. I may not find my body beautiful, but eyeball fluid sure is interesting. While we're on the topic, body-fluid in general is fascinating. So many different types and colors! I don't think my stretchmarks from pregnancy are beautiful, but they're on my stomach, and my stomach houses my organs in it, so that's neat.

I remember a phone conversation I overheard years ago. I don't have a context to give, because I was given no context. My short, squat coworker blurted into her cellphone, like a dare: "So what I'm built like a Teletubby?" I, of course, laughed. The defiance! The unexpected imagery!

I myself am not built like a Teletubby. I have the tub, but my proportions are different. But like those infernal creatures, I loom large. I feel oversized. 5'10". Giant lady. Size of a man. Woman built like a sin. Not all tits and ass and thighs, not anymore, which, of course, we all knew was going to happen anyways. And in my bulging, growing belly is a television. In it, you can see whatever you want.

Of course, I am only human. I would rather everyone who ever met me found me breathtaking. As a woman, I am keenly aware of pretty privilege—and, here, "pretty" obviously means thin. In an article for Glamour on the TikTok hashtag #prettypriviledge, Lilly Delmage writes:

Pretty people are perceived as smarter, funnier, more sociable, healthier, and successful. This places them at an advantage in employment, making friends, and—quite simply—being treated with basic human decency. Pretty people hold the key to a door of opportunities, connections and choices which are shut, locked and barricaded from others.

I want that life. I do alright for myself, I always have, but, of course, I want to be perceived as the prettiest and therefore the best person in the room. But at the end of the day, my credo still holds: Your opinion is not important. I am not responsible for your opinion of me and my body. That is not my business. You don't matter to me.

This essay is not brave. Do not call me brave. I have been called brave for wearing shorts, for wearing crop-tops, for going to the gym. Think about how that makes someone feel—to be called brave for admitting to having a body, an average, American body at that, and bringing that body into public sometimes.

This essay is defiant. It is angry. This essay is about how a doctor looked at me, said I should loose 200 pounds, and if I lost 200 pounds, I would be dead, and I don't want to be dead because my life is worth living.

In the snapshots section, I thought about using second person to generate sympathy, really put the reader in my shoes. Because even fat people have trouble empathizing with fat people about fat issues. Oh, those problems are for fat people, the others, the rest, not mildly tubby girls like me. But then I realized if I wrote in second person, I would be doing the same.

But since we—myself, the doctors, society—have a hard time looking at me, let's look at me backwards and upside-down. I will make myself bite-size if I must. Because we live in a capitalist society where junk food is half the price of healthy food. I will, too, make myself consumable by altering my ingredients.

You are dead. You donated your body to a cadaver lab to advance science and teach medical students and the occasional junior-high class. Your body is splayed on metal, your blobs of fat dyed yellower for more visibility. Only one visitor thinks to wonder what you died of. But it doesn't matter what people think of your body, you realize, because you're no longer in it, so what difference does it make?

Before you died, you had at least two children. Two came from your body. Maybe others did, too, if they exist, or maybe you adopted because you didn't start having children until a little later in life. For the viable pregnancies, one doctor thought you were very fat, the other didn't mention anything. One pregnancy was a false start, but your children that do live are beyond what you ever could have imagined, and you would do it all again, yes, even the loss, if you had to.

When and before you had children, you had a husband. He loved you very much. He remembers he thought you looked so beautiful walking down the aisle in your off-white dress, he teared up a little, in front of the fireplace in the first home you shared.

Before you had a husband, you were in high school, eating a bell pepper for breakfast because you were starving yourself. You had plans to vomit it out later. The adults in the overseas summer program are unintentionally cruel to you, but at this point, you are used to it, given the deliberate cruelty at home. You try not to let it bother you, because you're writing your best poem you've ever written, about language and candles and about having too much to say about that which cannot be said. You have work to do.

Before you were in high school, you were a child, eating off the adult menu, maybe for the first time. There are so many things you would like to try.

Before that, you were a smaller child, a baby really, at 23 months. You want everything the world has to offer—even if it's hospital Jell-O.

To be more precise than previously stated, the average human skeleton weighs 22.5 pounds. Which means that if I has reduced all the way to my bones, I would still have to give up something of myself. To lose 200 pounds, all my flesh, fat, muscles, and organs would have to fly off somewhere, and then I would have to keep going. Even in death, my body would be deemed too much and not enough at once. Perhaps ribs weigh half a pound. I don't know. I was never good at that life sciences class. But those can go. They will grow into someone stronger. They will grow into something unimaginable, a new species of woman, one that does not need you or your gaze.

When I die, what I want is for animals to eat me. People get appalled or think I'm joking when I express my last wishes. Of course, I wouldn't want my loved one tasked with taking care of my remains to be overly burdened or run into legal issues. But presuming this is perfectly legal, I would like my body dumped in a forest somewhere, not even buried. Undress me so I look like I've just been born. Let the wolves and the rabbits and the deer disappear me—yes, even herbivores will eat meat. Let the worms and the maggots and insects and vultures come to me. Let them undo me. That way, even after death, my body can keep giving and giving. It always has.

Bibliography

• "Average Dress Size by Country 2024." World Population Review, 2024. (No author cited.)

• Carlan, Hannah. "Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia by Sabrina Strings, NYU Press, 2019." CSW.UCLA.EDU, 2020.

• Cristel, Deborah A. and Dunn, Susan C. "Average American Women's Clothing Size: Comparing National Health and Nutritional Examination Surveys (1988–2010) to ASTM International Misses & Women's Plus Size Clothing." Taylor and Francis Online, 2016.

• Delmage, Lilly. "Pretty Privilege is Real—It's Time We Talked About It." Glamour, 2022.

• Fratello, Jenna. "What's 'Average'? Size 16 is the New Normal for US Women." Today, 2016.

• Loffhagen, Emma. "Millennials were Traumatized by Nineties Fatphobia." Yahoo Finance, 2021.

• Manne, Kate. "Doctors Have Fatphobia, too—which Does Serious Harm to Patients." The Washington Post, 2024.

• O'Mara, Ashley. "Fasting, Fat Shaming, and Finding Christ in My Body." American Magazine, 2018.

• Rodriguez, Angela C. Incollingo, Smieszek, Stephanie M., et al. "Pregnant and Postpartum Women's Experiences of Weight Stigma in Healthcare." BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 2020.

• Ryan, Lisa. "The Average American Woman Now Wears a Size 16, According to New Research." The Cut, 2016.

• Tali, Didem. "The 'Average' Woman Is Now Size 16 Or 18. Why Do Retailers Keep Failing Her?" Forbes, 2016.