As Anthonie rode the bus west out of the city, the riders grew fewer and the air crisper and the trees greener, statelier, healthy with the spring weather. Slouching in his seat, he peeled open a stick of jerky and snipped off small bites, then pulled a honey bun from his pack and consumed it in four or five swallows. Also in his pack was a can of energy drink, his vape, and a pair of snug black gloves he'd taken from a lost and found at a YMCA he often stopped at for free apple juice. People liked a valet who wore gloves because they didn't want some kid's grubby hands all over their steering wheel and shifter, and Anthonie, for his part, preferred to avoid the exotic rich-people germs spread all over the interiors of the luxury cars he parked. He was working for the same two guys he always worked for these days, a pair of one-time college linebackers who handled security and doorman duties while Anthonie zipped back and forth like a greyhound, parking one European sedan after another. Normally, two valets were needed for these types of events—some year-end party at a fancy college—but Ron and Stevie could skimp, only paying one valet, if that valet was Anthonie Dorien. They'd originally hired him to do security like they did, but he was only 5'9" and apparently had a baby face. It was a hard thing to confirm or deny about yourself, whether you had a baby face, but years and years of girls had backed up the assertion. They'd tell Anthonie he had soft little-boy cheeks and big, innocent eyes and then begin pawing at his zipper.

The bus driver called out to two high school kids in the back to put that weed away before he hit Frederick Avenue. The bus was nearly empty now. Hewitt. Thomason. At the Newell stop, the boys stepped off, trailing a pungent cloud. It was just Anthonie and an old blank-eyed guy in a Christmas sweater who probably wouldn't get off until he was forced to, a lost elderly soul with no better way to burn his hours than riding public transportation. No one got on at these suburban stops. Everyone out here had a car. In this part of the world, the pastel-hued store awnings exuded composed optimism, as opposed to the garish awnings in Anthonie's neighborhood competing desperately for the attention of worn-out passersby. This was a world where stunning women jogged the streets in perfect makeup and $200 sneakers. A world where no one loitered on corners or made camps around park benches. A world where everyone was welcome somewhere.

Anthonie had parked 35, 40 cars. It was night now. Sweat cooled on his skin as he crouched on the quiet side of the sprawling red brick estate and hit his vape. He could hear music from inside, pop songs from the 90s the partygoers listened to nostalgically. He could hear voices and ice clinking from the back patio or veranda or lanai or whatever rich people called their elaborate personal stoops. The air smelled of what Anthonie guessed was honeysuckle. In the near distance, the property's edge was marked by a low stone wall he could've hurdled.

A noise from behind Anthonie startled him. For a moment, he saw only a silhouette against the light from inside, and then a white-haired, squinting man closed the door behind himself and stepped onto the dewy grass. Anthonie rose slowly so he wouldn't give the guy a heart attack. His visitor was old—maybe 65, maybe older.

"Evening, sir," said Anthonie.

The man inclined his head a moment. "You're the valet."

"That's me."

The man stepped toward Anthonie. He walked with a painless limp. A graceful limp. A limp of luxury. He wore a tweed jacket and a tie, but also puffy basketball high-tops. When he raised his cigarette and struck a match, Anthonie felt comfortable hitting his vape again, releasing a little cloud of mist into the night.

"Those things look ridiculous," the man said.

Anthonie didn't know what he was talking about until he saw the old guy staring at his neon green vape pen with disdain.

"Can you imagine Humphrey Bogart using one of those contraptions?"

"Who's Humphrey Bogart?" Anthonie asked.

The man shook out his match. "Tell me you're kidding. If you're not, lie to me."

"I'm kidding," said Anthonie. And it was true. His grandmother had loved Humphrey Bogart. The Big Sleep. The Maltese Falcon.

"In my day, we took up smoking because it looked cool. Why else would you start? Why spend the money?"

"You're the authority on looking cool?"

Now the old man had to figure out where Anthonie was looking. "Ah, yes, my footwear. I need the stability of old-people shoes, but I refuse to wear old-people shoes. I'd rather appear a stylistic vagary than a helpless geezer. Perhaps you'll understand, one day."

"What's a vagary?"

"An unexpected or unexplainable anomaly."

Anthonie nodded. He took one last hit, then put away the vape. He knew the old man was right. Cigarettes were cooler. Everyone knew it. So what?

"Are you, like, a professor?"

"I am indeed."

"What of?" Anthonie asked.

"Music."

"Oh, yeah—what kind?"

The old man took an indulgent drag and let the smoke leak out his nostrils. He adjusted his glasses with swollen-looking fingers. "The kind no one listens to anymore."

"Like oboes and cellos and shit?"

"Precisely."

"You teach people how to play Beethoven?"

"I teach people how to listen to Beethoven. I'm not interested in playing. When it comes to artists and critics, a clean division of labor is indicated. Everyone wants to be the star nowadays. Everyone wants to be seen. Isn't that what people your age say—I want to feel seen?"

"We like to feel seen and we like to vape. That pretty much sums us up."

A crash of glassware was heard from back behind the house, followed by a swell of laughter. A chill went up Anthonie's spine, his polo shirt offering scant defense against the dropping temperature.

"When I was little, I could play Brahms on a recorder," he offered, surprising himself. He hadn't mentioned that to anyone in a long time—not that it was some big secret.

"What piece?" asked the old man.

"I don't remember the name."

"Whistle it."

Anthonie made two false starts, feeling self-conscious, then found his way through a couple bars of the music, humming instead of whistling when the notes went low.

"Hungarian Dance #5. He wrote that while out of his mind with fever."

"A guy at my grandmother's church taught me, then he moved away. Pretty soon after that, my brother broke the recorder in half."

"Broke it on purpose?"

"I didn't see it happen," said Anthonie. "Could have been on purpose. He didn't really like when I..."

"When you what?"

"He didn't like I could learn things like that. And school things. Math. I could memorize. I could write."

The old man had already smoked his cigarette to a nub. Anthonie watched him flick the butt out into the night, watched it land, cherry still hot, on the pristine lawn.

"Do you go to Renworth?" the old man asked.

"I don't go to any college. I'm getting by on high school smarts. Getting by on tips."

The old man gave him a smirk. "Probably for the best. Decent chance you'd wind up doing the same thing you're doing now, but with $150,000 in debt."

The professor looked off. He didn't seem to expect a response from Anthonie, which was convenient because Anthonie didn't know what to say. It was true he hated debt. Of any kind. He had enough money saved for a healthy down payment on a car, but didn't want to be saddled with the monthly note. Owing hundreds of thousands of dollars was not something he could get his mind around, especially since he'd once been all set to attend college for free. Once you get used to the idea of something being free, paying for that thing is not a welcome notion. Once you blow out your knee before your senior season of high school and watch three scholarship offers evaporate, it's hard to even glance at the normal-student sticker price.

"Why are you out here?" Anthonie asked the old man. "Instead of with the other guests."

"A fair question, since I've trespassed your moment of leisure." The old man gave each of his jacket sleeves a tug and then tucked his hands in his pockets. "The answer is as follows: I don't wish to be spoken of as a recluse or misanthrope, even if such accusations have merit, and so I attend a minimum of these events, exactly enough to thwart narratives that might take purchase regarding my disposition. In this case," he said, rolling his eyes in the general direction of the three-story edifice looming behind them, "the soiree honors the retirement of a colleague I'm thought to share a contentious history with—this based on very little, but it doesn't take much at a small liberal arts college to constitute a rivalry. By attending this party and making a toast to the departing, which duty I've already performed, I've robbed certain faculty of any opportunity to gossip about Professor Reichart and Professor Friis not getting along."

"Wow," said Anthonie.

"Yes, wow."

"People get robbed where I live, but not usually of opportunity for gossip."

The old man smirked a second time. "You're funny."

"Which one are you? Reichart or Freeze?"

"Friis, not Freeze. Kasper Friis." The professor pulled his right hand from his pocket and offered it, and Anthonie shook. The hand was soft, but also stiff and cold.

"I'm Anthonie." He didn't say "with an ie." It wasn't something he usually volunteered.

"Hey, can you do me a favor and have my car waiting out front at 9:40? I'm going to sneak out at 9:40. I don't want to be waiting around on the steps and get snared in a chance interaction."

"The old Land Cruiser, right? I don't think I ever valeted a car with that many miles."

Professor Friis handed him the little ticket. "It's loud and smelly. My neighbors hate it. Therefore, I'll never give it up."

"You're a people person, aren't you?"

"9:40, okay?"

"Got it."

The old man clapped his hands and set his jaw. "Back into the fray," he said, and turned and limped gentlemanly to the door and disappeared back inside.

As he drove the unwashed Land Cruiser up the quiet lane, noxious smoke billowing out behind the vehicle, Anthonie thought of something a high school English teacher had once told him. Anthonie had stayed after to make up an in-class essay he'd missed because his grandmother was sick, and the man had read the essay right then—about a poem that went on and on about a nightingale—Anthonie sitting and waiting in the hard desk, and had nodded thoughtfully when he was done and told Anthonie college would probably, because he was actually interested in critical inquiry rather than mere regurgitation, be a waste of time for him. The man had not been a good teacher at any point in the semester, but since the holidays had been wearing gym shorts and ballcaps to school and barely planning out his classes. Anthonie had pressed him to elaborate, and the guy had mumbled unless Anthonie enrolled in courses for welding or nursing, he could teach himself better than the professors could. The man knew about Anthonie's situation, the wrecked knee and the scholarships getting pulled, so maybe he was trying to make him feel better. What Anthonie knew for sure was that now, in his present life, he wasn't doing a good job of teaching himself anything. Besides which street corners to avoid at night, and what time he needed to rise if he wanted a hot shower, and there was no safer place to hide his cash than tucked behind his humble 22-book library—besides those things, he wasn't learning a whole hell of a lot.

He taxied up the drive at 9:38. The instant he hopped down from the high-perched seat, Friis appeared and slipped him a $5 bill.

"Have a good evening, sir," Anthonie said, raising his voice over the rumbling, chuffing engine of the Land Cruiser.

Friis, instead of stepping toward the driver door, leaned toward Anthonie. "How much you get paid for a gig like this?" he asked. "Not including tips."

Anthonie paused, then went ahead and told him. $125.

"Proposition. I'll give you $200 to carry some boxes up from my basement. Take you perhaps two hours. None of it's that heavy, but it's awkward. The boxes and my asking you to carry them—they're both awkward."

"Your basement?"

"Conventionally I'd get a student for this genre of task, but then they'll want me to write a letter of recommendation or something. Tit for tat. I'd rather pay money than write anyone a dishonest letter. Or an honest one, for that matter."

Anthonie wasn't exactly in a position to turn down a $100 an hour. He felt rushed to answer because the car was so loud and its dark exhaust was rising thickly into the white blossoms of a flowering tree. He shouldn't have felt rushed. It wasn't his car or his tree.

"Make it $250," he said. "I have to take the bus 30 minutes each way."

"That's the spirit," said Friis, clapping him on the shoulder. "That's the old entrepreneurial gusto. If Monday is conducive, it's 14 Foxwood Way."

"You're not luring me over so you and your friends can chain me to a wall, are you?"

Friis chuckled. "I don't have any friends. You think I could chain you to a wall myself?"

Yuri Gagarin, the first human to travel in space, went 17,000 miles per hour. Galileo named the four moons of Jupiter the Medicean Moons, in hopes of winning the favor of the Medicis. Gaugin's The Yellow Christ,a typical example of the Pont-Avon school, employs apparently arbitrary primary colors. Genghis Khan, whose father was poisoned by rivals, promoted literacy among the people he ruled. Geronimo's real name was Goyaale, which means "the smart one." The term Peeping Tom was coined when a tailor peeked through a window at the naked, horseback Lady Godiva.

Friis' house was maybe eight blocks from the bus stop, and during those eight blocks Anthonie saw five people, two of them babies in strollers whose faces he didn't actually see. He counted the house numbers upward—no address was marked on Friis' mailbox, only a faded stencil on the curb. It was eerily quiet, birds responsible for the only noise, and when Anthonie started up the long, buckling driveway obscuring itself into maples and pines, he felt like a trespasser, like he was on camera, watched. The yard beyond the barrier of trees was patchily mowed—the old guy was probably still doing that job himself. Beside the house was a stone well looking like a relic, and in the distance behind the property vast plowed fields were spread like quilts. The house itself wasn't grand like where the party had been held, but it wasn't little. It was composed of a dozen different building materials—brick, stone, stucco, wood, vinyl siding—and the plants in the flowerbeds were long dead.

Anthonie stepped onto the porch and rang the buzzer, keening his ear to make sure it was operational, and in the quiet moment that followed, he was struck with the fear the old man wouldn't remember him, wouldn't recall their conversation at all. He heard a shuffling inside, and then the door creaked open, and here was Friis, in a gray tracksuit with his shock of white hair, moccasins on his feet and an oven mitt on one hand.

"They say kids today are never on time and don't want to work," he said, "but look at you dispelling stereotypes." He turned breezily and waved a hand for Anthonie to follow, and Anthonie stepped inside and shut the door and trailed Friis—almost a pimp walk, his gait, like kids in the schoolyard used to do for laughs—down a narrow hall whose walls were adorned with paintings of boats as sea: a warship, a fishing vessel docked in the cold, a single wretched man in a wooden dingy.

As they passed the kitchen, Friis said he was making a curry—that explained the smell in the house—and stated as a casual fact that Anthonie would stay and eat when he was done with his work.

"Oh, no thanks," Anthonie told him. "I'm not really hungry."

Friis stopped walking and turned to face Anthonie, a look of threadbare tolerance on his face. "You don't like curry?"

"I haven't had it in a long time. There's an Indian place a couple blocks from me, but it's expensive. When teenagers walk by, which the lady thinks I am, she puts on the skunk eye."

Friis shook his head and released a forbearing sigh. "It's homemade," he said with theatrical patience. "It took me all day to make. It's the best food in the world. What foolish decivilized instinct is telling you to deprive yourself of this meal and insult me, your host, in the process? It's amazing what you kids need to be taught. No, it's not going to taste like French fries from Burger Hut and Zombie soda drink. It's traditional cuisine, nourishing and delicious. What principle are you operating on that you would turn it down?"

"Geesh. I'll try it," Anthonie said. "Don't blow a gasket. I'll be civilized and try your curry."

Friis made a palms-up Lord-give-me-patience gesture. "He'll try it, he says. Wonderful."

"Anyway, you're my employer, not my host."

"I'm both, okay? I'm striving to be both."

"What's Burger Hut? It sounds good. It sounds up my alley."

"They're all Burger Hut. The world is one big Burger Hut."

Friis turned and kept on down the hallway. He rounded a corner, pushed open a flimsy door, and identified this as passage to the basement. He reached in and flailed his hand about for a light switch and finally found it, but made no move to descend the stairs.

"Everything on the floor, bring up. If it isn't on the floor, leave it."

"On the floor, bring it up," repeated Anthonie.

Friis started back the way they'd come, then veered into another hallway and opened another door, this one to the garage. He instructed Anthonie to pack a load at a time into old Elsie and dump it by the mailbox. "It's all getting picked up tomorrow for junk—just stack it by the curb."

"Elsie?" said Anthonie.

"L.C. Land Cruiser. It's a whimsical nickname lending my longtime automobile the emotional import of a pet or human friend." Like the other night when he arrived at the party, Friis held out his key ring—a meager assemblage of three tarnished keys and a pewter bottle opener—and dropped it into Anthonie's waiting palm. "And people say I'm no fun. Me, a nicknamer of cars."

The boxes, which numbered maybe four dozen, weren't heavy. Anthonie was able to haul them up the steep stairway two at a time and fit six or seven in the back of the Toyota at once. As he passed back and forth through the house, Friis was often in the kitchen, humming something doleful and tending his curry and sipping what appeared to be a vodka drink. Up the stairs and down. Up the stairs and down. Anthonie's leg muscles felt taxed in a way they never felt jogging for cars. His heart thumped, sweat trickling under his shirt. When only a couple loads remained, he paused to rest and idly peeled back the cardboard flap of one of the boxes. Musty clothes inside. Flouncy clothes. Blouses. He peeked in another box and saw a few old pairs of shoes, men's and women's, a tangle of costume jewelry and ten defunct remote controls. It seemed there had once been a lady of the house, a suspicion confirmed when Anthonie checked a third box and found several framed photos of the same woman, all from the same era—the hair said the 1980s. The woman's face was sweet, good-natured, her eyes guiltless behind large, blue-framed glasses. Anthonie, as he went to return one of the pictures to the box, was startled out of his skin by a clattering, reverberating crash seeming to come from directly above him, shaking the whole house—a loud clanging and then something round and heavy spinning on its edge, around and around until, finally, a crescendo into dead quiet. Anthonie instinctively crouched like in the city when a gunshot rang out. He dropped the photo back in the box and fumbled to re-close the flaps. The kitchen. It had to have been the kitchen. Anthonie took the steps up to the main level three at a time, rounded the corner from the hallway—when the kitchen flashed into his vision, the color of the floor wasn't right. The odor of curry hit him like a wave. The old man, on the floor, still clutched one handle of the enormous pot, like a man grasping a life raft. He was groaning. He was trying to get a full breath, cursing quietly in a language unknown to Anthonie.

"It's okay," Anthonie said. "It's okay. Hang on—let me help you."

But Anthonie was frozen, taking in the sight of the kitchen, the floor splashed with slick, mustard-colored sauce working its way toward each wall, splatters on the cabinets, even on the ceiling. The old guy—Anthonie couldn't recall his name at the moment—disentangled his fingers from the pot and tried to prop himself up on an elbow, but he fell right back down, whether in pain or from slipping in the curry, Anthonie couldn't tell. The old man's sweatshirt and hair were completely drenched and discolored.

Anthonie kicked his shoes off behind him, well clear of the mess, and as the old man had said at the party, entered the fray, trying not to slip and fall himself. He hoisted the near-empty pot into the sink, reached back down for the big spoon and an oven mitt Friis—that was his name, Friis and not Freeze—had lost in the fragrant swamp. Anthonie knelt and lightly gripped the old man's arm, and Friis let out a whine.

"Other arm," he huffed, returning to English. "Other arm."

Anthonie sidled around and drew him up and helped—well, basically carried—Friis over to the far wall, where a low stool sat, Friis spitting epitaphs about idiot fucking Mexican tile you had to have because your idiot friend Betsy got it. If Betsy got Ebola, you'd want it, too. If Betsy got audited by the IRS...

"What's wrong?" Anthonie said. "Where are you hurt?" Friis could barely keep his eyes open, but Anthonie didn't see blood anywhere.

"Cold water. Pour water on my leg. This one. The left."

Anthonie went for the pot, then thought better of it. When he looked back at Friis, he was pointing at a low cabinet. Anthonie shuffled over and found a pitcher and filled it and slowly dumped the cool contents over Friis left thigh, directly on his sweatpants, and Friis nodded in relief. He sat stiffly, cockeyed on the stool, and when Anthonie tried to pull him straight, he hissed. He held one arm pinned against his chest like it was already in a sling, and with the other he tugged at his pant leg, making little headway.

"Check the burn," he was saying. "Look at the burn."

Anthonie steadied him and helped him pull down his sodden pants enough to view his leg, which besides being shockingly skinny—Anthonie's mind flashed to his grandmother's legs at the end—and red and splotchy, didn't seem burnt in any grotesque, horror-movie way.

"Let me set you down on the floor," Anthonie said. "You're gonna fall."

"Jesus Christ," said Friis. "This side is throbbing, this side I can't feel."

Anthonie lowered him groundward, Friis bracing against the counter, his body shaking. Anthonie could feel curry between his toes—it had drenched his socks. He wasn't sure why he'd kept them on. Curry was in Friis' ears. He wore one moccasin, the other nowhere to be seen.

"This damn knee," Friis said. "I can't use it. I can feel it swelling up like a cantaloupe."

"I'll call 911," Anthonie said, wiping his hands on his shirt so he could fish his phone out of his jeans pocket.

"No!" Friis shouted, his voice breaking. "No—don't do that!"

The old man slipped all the way down and then righted himself to half-sitting, looking like he was attempting some difficult stretching pose. "Don't call them. Please don't call them."

"Why the hell not?" Anthonie said. "You probably broke something. You probably broke a bunch of things."

"I'm begging you not to type that number."

"Your knee's messed up. Your arm's messed up."

"Whatever's wrong with me, I don't want those quacks."

"What quacks?" Anthonie said. "What do you mean?" He was pinching his phone with two fingers, sliding it out of his pocket, but Friis' desperation had stopped him.

"You don't understand," Friis told him, grinding his back teeth. "They'll never let me come back here."

"Come back where?" Anthonie had the phone out now, and Friis glared at the device like it was a match in an oil refinery.

"They'll never let me live alone again. They'll put me in geezer jail. Don't you get it? They'll put me in a little off-white room and turn on the soap operas and feed me spaghetti with an ice cream scoop. Please, man—have mercy!"

Anthonie pressed the 9 and the numeral appeared on the screen. He didn't want any guilt in this situation, didn't want anything to be his fault—did he accomplish that by calling or not calling? "You took a nasty fall. You could have internal bleeding."

"If I do, so be it." Friis raised his working hand to his forehead to mop his sweat, but mopped on a streak of curry. "They'll bulldoze this house. They'll sell the land to pay for my jail cell. You finish dialing those goons, you might as well kill me right now. I'd prefer you get one of those steak knives and slit my throat. Death doesn't scare me. Just slice through my carotid artery. Go ahead—grab a knife out of that block right there."

Anthonie erased the 9, no idea what to do. He had not taken the #17 bus out here so he could ruin his clothes and be power of attorney for some classical music curmudgeon.

"Let me call somebody," he said. "Let me call your ex-wife or whatever."

Friis looked confused at that, a sneer overtaking his face.

"The lady who needed the tile from Mexico," Anthonie said, rather than mentioning the pictures he'd spied in the box.

Friis scratched his neck savagely. "She's been dead to me for decades, and thankfully now she's dead to everyone. I don't think you'll be able to reach her beyond the grave."

"What about kids? You got a kid I can call? That's who should be dealing with this. I mean... helping you."

Friis coughed and clutched his ribs. "Stop making me argue," he said. "Stop fucking debating me."

"How about, like, a student or another professor? Someone at the school?"

"I don't want you calling anyone," Friis wheezed. "Let me get my bearings. Quit trying to seal my fate, you ghoul."

The old man tried to rise again and immediately crumpled. Anthonie steadied him by the shoulder as gently as he could.

"What then? What do you want me to do?"

"Look," Friis said. "I need to get to the bathroom. I need to get to the tub and clean off." He reached and gripped Anthonie's bicep, tighter than Anthonie would've thought he could. "I need to get cleaned up and get to that sofa right in there. Then I can sort this out."

"The bathtub?" Anthonie said. "You can't even sit up straight."

"Just get me to the bathroom, and I can manage. If you help me to the bathroom—" Friis winced, as if his own breath were doing something terrible to his organs. He was angry, but not at Anthonie. Angry to be begging for help, probably. When he spoke again, his voice was even, a bit defeated. "Let's not make a big deal out of this," he said. "I'll give you an extra $200 dollars. Once I'm cleaned up and on that sofa, another $200."

Anthonie wasn't sure what kind of look he was giving the old man, kneeling close and gripping his brittle-boned shoulder. Outside the window, the shadows were thickening. Panicky birds flashed back and forth.

"You don't have to dress or undress me, okay? Toss my robe in the bathroom. There's a robe on a hook on my bedroom door. Just leave me on my sofa. Don't make me a ward of the state. At least not yet."

Friis moved his hips laboriously, shifting his position in preparation to stand, and Anthonie smelled, mingled with the curry, the anomia stink of urine. Instantly, this softened him. His grandmother had wet herself over and over the last weeks of her life. Anthonie would try to stay calm when he talked to the nurses—inside, he was beside himself at how long they took to change her. He himself had been a ward of the state in the months before he turned eighteen.

"Fine," Anthonie said. "$200. The tub then the couch. I don't know what you think you're going to do after that."

"Me, neither," said Friis.

Anthonie shook curry off his fingers. "How much of this shit were you making?"

"I freeze it," Friis said, almost to himself. "I freeze it, then I can eat it for weeks."

"I could gouge you right now, dude. I bet you'd pay a lot more than two bills."

When Friis looked him in the eyes, Anthonie was sure he saw the already familiar smirk hidden under the old man's grimace of pain. "You could, but you're not that type of person."

A laugh escaped Anthonie. He wanted to help this old guy, but whether it was because he was a good person or just pitied the poor asshole was hard to tell. The guy had nobody because nobody could stand him, and here he was begging for help from a complete stranger.

"Are there towels in that bathroom?" he asked Friis. "I'll make a path on the floor so you don't have curry all over the rest of the house."

"That's the spirit," Friis managed. "That's the old optimisme juvenile. That's the plucky valet I know."

While Friis washed up and took stock of his injuries, Anthonie, for lack of knowing what else to do, brought the remaining boxes from the basement out to the street, driving the dinosaur SUV down the drive and back through dusky, yellowish, pollen-laden air. He was barefoot, shirtless, feeling now the opposite of what he felt before: he didn't feel watched; he felt completely off the world's radar, in some kind of bizarre dream. Back in the house, he opened a couple windows for the smell and tiptoed over to the bathroom and listened at the door—Friis was grunting, but he seemed to be getting along as well as could be expected.

On his way back to the kitchen, Anthonie picked up the towels one by one. He dropped them all on the slick fucking Mexican tile to absorb what they could, then found sponges and a bucket under the sink and started scrubbing, hands and knees, giving up on his jeans. He knew it was a strange, indefensible action—slaving away with suds to his elbows in this old guy's kitchen, this stranger who had no right to ask Anthonie for anything he wasn't willing to pay for. His roommates would've cackled at him, toiling away like Cinderella. At the same time, he knew he wouldn't have to defend the decision because no one would ever know he'd done this. He only had to defend it to himself, and he wasn't in the mood for defending decisions right now—he was only in the mood to clean this kitchen. His jeans had cost him $60 on sale at Marshall's. He was actually paying to clean this kitchen. It was a net loss.

When the white sponge was bloated and stained a deep saffron, Anthonie dropped it back in the soapy water and got to his feet. He pulled out his vape and hit it. Friis wouldn't know, across the house and occupied with self-doctoring, and how much leverage did the professor have to protest anyway? The nicotine went straight to Anthonie's blood and mellowed him a tick. He leaned on the counter and gazed out the kitchen window at a blue jay fussing with its nest. It was close, not 25 feet away. Only half its feathers were blue, Anthonie was surprised to observe, but the thing was beautiful. With birds, the males had to be pretty. Same as Anthonie. An elementary school teacher, an old lady—she'd seemed 100 at the time but was probably younger than Friis was now—had told him this, that boy birds had to be pretty so the girl birds would choose them. She said Anthonie was going to have no problem in that department.

He turned from the window and poked around the half-clean kitchen for a soda. He knew Friis wouldn't have a Monster or a Red Bull, but maybe he kept cans of Coke for guests. Well, what guests? Maybe 7UP for mixing cocktails. Anthonie opened the fridge, taking a moment to clean splatters off the front of it with a rag, and found no soda inside. He checked the pantry. The cabinets. There was olive oil from Spain. Wine from France. Coffee from Africa. But no soda pop from Atlanta, Georgia.

Anthonie found a glass for water instead. As he reached for the tap, he heard the muted, old-fashioned ring of a telephone—brrrrring, like in a movie. Quiet, then the next inevitable ring. He padded across the tile, out the back of the kitchen and onto plank wood flooring. Around a tight corner he saw a small shelf built into the wall and on the shelf a blocky, beige rotary phone and an answering machine the size of a small pizza box. The phone called out again, and a fifth time, then the machine beeped and a woman's voice filled the alcove, at once apathetic and impatient: "Well, happy birthday, Dad. The big 71. I guess they're all big, after 70. As you know from my letter, which was not my idea to send, I've been going to therapy—no, that doesn't mean I'm crazy—and it's done enough good that I gave into Paul's prodding and called you on your birthday. Yay for me. I'm not going to claim to look forward to talking to you one day—same as all these years, you know where I am and you have my number. I have no problem with you speaking to Meredith if you have the inclination, but you're gonna have to talk to me first. We're just living our lives over here. Another week underway." The woman blew a deep sigh into the receiver, like wind lisping past a flagpole. "I'll end by saying I hope your health is good. And that's true. I hope it is. Okay. Goodbye, Dad."

Anthonie listened to the click of Friis' daughter hanging up. He went to take a sip of his water, then realized he hadn't poured it yet.

"No," he said. "At the moment, his health isn't that spectacular."

It took Anthonie and Friis ten full minutes—two panting-against-the-wall rest breaks and several short pauses in which the younger man adjusted his handholds on the elder's elbow and armpit—to reach the faded, blue-checked sofa. As promised, Friis wore his robe, and might've looked like a retiree at a sauna if not for the bruising setting in along all his limbs, yellow-purple and spreading fast, and the tenderness with which he treated his swelling knee and busted shoulder and the smarting skin of his left thigh.

"I'm lightheaded," he said. "I need to sit here a while. I feel like I ran a marathon."

"You're not bleeding," Anthonie said. "That's generally a good sign."

"I'm hungry. I get dizzy when I don't eat."

"A lot of people get dizzy when they drink vodka and don't eat."

The old man flashed him a look.

"Is anything broken?"

"If it is, it's not bad enough they could do anything for it. Just give me pain pills so I can't think. It makes their job a lot easier if you can't think."

"What job?" Anthonie said.

"Locking you in a death camp. They call them nursing homes, but they're death camps."

Friis tugged a pillow out from behind him with significant effort and reached it feebly toward Anthonie, and Anthonie took it and tossed it in a chair.

"Nice outfit," Friis said, recovering his breath and struggling to look Anthonie in the eyes.

"As they say in Pulp Fiction, 'they're your clothes, motherfucker.'"

Anthonie wore an undershirt and a pair of bellbottom sweatpants he'd scavenged from a stack of folded clothes in Friis' laundry room. They fit strangely well. He pulled a footstool, an ottoman or whatever, over from the wall and positioned it in front of Friis so he didn't have to pull his legs up on the sofa to relax. He set the TV remote in arm's reach, and also a glass of water.

"I said I'd eat the curry," Anthonie said. "You didn't have to throw a big fit."

Friis' face changed. Not quite a smile. "There's a can of chicken noodle in the pantry. Can you heat it up for me? I have to eat or I'll keep getting weaker."

"Chicken soup," Anthonie said. "Okay, I can do chicken soup. I'll use the microwave."

"I don't own a microwave," Friis said through a tense jaw.

"Okay, then. In a pot, little water in it, right?"

"Not too much water."

"Let me ask you a question?"

"What is it?"

"How late do you think buses run out here, professor?"

Friis didn't seem to register this. He was testing his ribs with his fingertips.

"I'll tell you the answer," Anthonie said, gesturing toward the far windows which framed the falling evening, nothing visible in the dimness but the largest, palest tree trunks. "I'll tell you, since you've probably never taken the bus—the last one comes by in about eight minutes."

Friis put his forehead in his palm, miserable.

"Well, seven minutes," said Anthonie.

Friis closed his eyes tight a moment, then opened them and stared down at the floor. He picked up the remote control only to set it back down exactly where it had been. "Stay here the night," he said. He raised the hand of his good arm as best he could, anticipating Anthonie's refusal. "Just tonight. You can eat whatever you want. Drink whatever you want. One night."

"Except soda. Can't drink soda because you don't have any."

"I'll pay you, of course. What do I owe you now, $450? Make it an even $500 and crash here till morning."

"Crash?"

"I need you here. I need to eat. Sleep wherever you want. Sleep in my room if you want."

"I'm not sleeping in your room, dude."

Friis pulled the flaps of his robe closed like a modest housewife, then braced his pained elbow. "I said that because I'll be out here, that's all."

"I know," Anthonie said. "I'm messing with you." He could see one of the paintings hanging in the front hall, the one featuring a terrified man in a yellow hat, alone in a simple wooden boat, tossed by a great wave. He could see Friis' frail, blue-veined feet.

"You're saying make it $500—you're running up this baller tab but I haven't seen any money. I don't see dollar one in my hand."

Friis sighed. His face softened, conceding the point. He deliberately picked something off the checked pattern of the sofa, concentrating to keep his fingers steady, and dropped whatever it was down to the rug.

"I trust you," he told Anthonie. "I won't claim to have much of a choice at this juncture, but nonetheless, I don't trust a great many people and I trust you. In my gut, which is to say, in my brain, I judge you trustworthy."

"Happy to hear that," said Anthonie.

"Go in my room. There's a window seat. Down underneath there's a little drawer that pulls out—"

"Yeah, most drawers do that."

"There's money in there, under the counterpane. Go right now and take $500. It's in a plastic bag. Put five $100s in your wallet and stay here tonight. Bills, as you call them. Benjamins. I'll be stronger in the morning. Well, I'll either be better or worse. You can't make the bus, anyway."

"A night in the burbs," Anthonie said. He rubbed his eyes hard with the heels of his hands. "What's a counterpane?"

"It's a blanket," Friis said. "It's what an old crank calls a blanket."

Anthonie could feel himself giving way. He didn't want to sprint for the bus and leave this guy starving. He didn't want to sprint for the bus and miss it and crawl back here. He didn't want to sprint for the bus and catch it and spend a half-hour watching his surroundings degrade.

Friis endeavored to hoist one foot up onto the ottoman, lifting his leg with his good hand and squinting one eye with the effort. Anthonie knelt and easily raised the old man's gaunt legs one at a time, each weighing about as much as the bags of rice Anthonie bought at the discount store. He gently rested each gnarled heel on the supple leather.

"You're the only person who's ever known where that money is," Friis said.

"Well, I bet I'm the only person who ever tried to clean ten gallons of curry out of every corner of your kitchen."

Friis settled both his hands in his lap, the maimed one perfectly still and the other like a loose sheath around it. "No rules have been broken thus far," he said. "I only ask God never to take away my mind, so no rules of engagement have been violated."

Instead of bunking in the old man's bedroom, a creepy proposition even without the old man in there, Anthonie commandeered a space down past the door to the garage that could've been described as a library or a study or a gentleman's den, if gentlemen still existed. "Can I stay in that room with the books and records and shit?" he'd asked Friis, and Friis said he wasn't in a position to deny such a request and begged Anthonie to just please not break anything. The room featured a broad, cushy chair that was like sitting on a firm cloud. It featured a record player that, plain to the eye, was much higher quality than his grandparents' old player. When he'd finished his water crackers (saltines without salt) and his mineral water (soda without sugar) and settled himself cozily into the big chair, he realized two things. One, he was wide awake because he usually went to sleep around midnight and it was 8:45. And two, the professor didn't have wi-fi, and even if he did, Anthonie's phone was almost out of charge and he'd neglected to bring his charger because he thought he'd be at this guy's house two hours max. He set the phone on an end table of dark wood, next to an hourglass and a half-burned candle. A map of Austria hung on one wall. A chess set posed on a shelf. Anthonie could hear the old man snoring all the way from the living room and, more strangely, could hear no other noise, no car horns or drinkers yelling or babies bawling. Nothing but the rhythmic snores.

He rose and strode over and regarded the fireplace. It appeared to be a working, woodburning fireplace. A rack of logs on one side; on the other, tools hung—poker and brush and miniature rake. The mantel was cluttered with framed programs from operas the old man must've attended. A pair of Mardi Gras masks. A stuffed yellow bird on a plank. Anthonie had made a fire once before, on a camping trip to the Poconos for poor kids. He'd kindled the fire with pine needles and had tended it all weekend, adding hunk after hunk of sloppily split hardwood, strangely fascinated by the flames, hardly leaving the warm glow for more than twenty minutes at a time. The youth pastor running the trip had nicknamed him Marshall—like, Fire Marshall.

He wouldn't need pine needles tonight. There was a stack of old newspapers and one of those flame wands. Anthonie twisted a few sections of New York Times into tight rods and constructed the log pyramid he still recalled the youth pastor teaching him. In no time, he was gazing at a crackling blaze that drowned out the old man's snores and chased the chill from the room and cast its undulating, soothing light against three walls.

He went to a long shelf of records and selected one at random. His grandmother had listened to Julio Iglesias and Marvin Gaye and Tony Bennett, but this album was by Gustave Mahler. Anthonie switched on the player and placed the disc and sunk the needle in the groove. The volume was low, then too high, and then Anthonie found the perfect level and the tenuous strings began lapping over him like gentle waves. He didn't sit down. He felt calm—the music, the fire—but not tired. He felt soft-spined. On low alert. He was in another country, or another century. He'd been alive twenty-three years and had barely left the state, but right now he was in foreign territory. Leaning casually against a heavy, cluttered desk, he felt like he could have different thoughts, unfamiliar and important thoughts, but none immediately came to him.

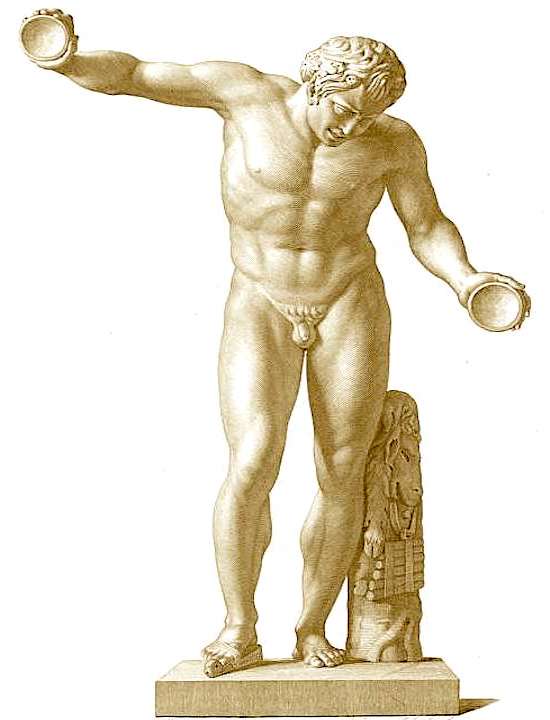

Anthonie spent a few minutes browsing Friis' concert stubs, matching the venues in Austria to the map on the wall, matching the other venues to a bulbous globe sitting on its own end table and whose surface was mottled to show mountain ranges and shaded with hundreds of colors for the countless nations. He drifted over to the chess set and lifted one of the weighted pieces. A rearing horse. This was pewter, Anthonie guessed, like the bottle opener on Friis' key ring. The little statue was so detailed, Anthonie could see the horse's fierce, noble eyes and the decorative crests adorning the saddle. No rider, but the piece was called a knight. Anthonie knew that much. The board was checked with jade and blond wood. Twenty pounds, probably, but Anthonie didn't move it. He replaced the knight between the castle turret—that one was called a rook—and the fancy-hatted fellow who had to be the bishop.

The warmth from the fire did its work and soon enough Anthonie was drowsy. He cracked the window to let in the night air, and went and curled up in the big chair without need of a blanket—or a counterpane. He could hear the fire cracking its knuckles. He could hear, very faintly now, Friis' snoring. He could hear crickets from outside.

As he drifted off, his mind, despite him, wended toward thoughts of what a fool his friends would think he was—what a fool for not robbing this rich jerk blind and disappearing into the night. He hadn't counted the money under the window seat, but it was several thousand. And he had not yet missed his chance. He could do it right now. This minute, he could rise from the cushions of the chair and sneak across the house and clean the cash out and leave nothing behind but his ruined jeans and a smoldering fire. His roommates would never comprehend why he wasn't doing this, and he didn't fully comprehend it himself. His grandmother wouldn't approve, but he'd done plenty of things his grandmother wouldn't like. He'd quit church. He'd played lookout for Remy and his guys a half-dozen times. Shoplifted. Hopped a hundred turnstiles. Anthonie knew what it was. It was that the crusty bastard said he trusted him. The sly old coot. He said he trusted Anthonie, and he'd seemed to really mean it.

Next thing Anthonie knew, he was waking up, blinking, wondering where he was. The smell of fresh pine was wafting in the window he'd left open, like a taxicab air freshener except the real thing. Morning light was in the boughs outside, small birds whickering back and forth in the velvety green. The coals glowed faintly, red-orange, in the fireplace. It had been a while since Anthonie had slept through a night without something waking him up—Mondays and Thursdays, the dumpsters getting banged empty in the lot adjacent his building; on weekends, one of his roommates careening in loudly from a night out; neighbors fighting; sirens. After peeling himself out of the chair and slipping the Mahler record back into its sleeve and the sleeve onto the shelf, he ambled out to the living room and found Friis awake and the TV on. The look on the professor's face was one of disdain—whether due to his pain or the content of the used-car commercial he was watching, Anthonie didn't know. He could see right away the old man's bruising had spread. He told his host good morning and Friis nodded. Friis was calm, composed, but his eyes were glassy and he held his head at a more pronounced tilt than yesterday. Anthonie went and refilled his water glass and handed it to him—at the first sip, he began coughing, and the hurt from the coughing doubled him over.

"I'm going to have to, uh..."

"Oh, right," Anthonie said. "The bathroom."

Friis handed back the water glass, still mostly full. "Just get me over there. I can manage if you get me over there." He coughed again, then took a moment to test whether his head would turn. He worked his jaw. Massaged his midsection with his fingertips. "You must be famished," he said. "Facing down mortality has made me forget my manners. Did you sleep well?"

"Better than ever," said Anthonie.

"You'll find eggs in the fridge. Get me to the men's room and then go ahead and make a quantity of eggs. We'll partake of a feast."

"I don't really like eggs," Anthonie admitted.

The old man stared at him blankly. "I don't understand what you mean by that."

"It's okay," said Anthonie. "I'm not really hungry. It's too early."

"What in God's name...you know what, never mind. I need to conserve my strength. I can't explain right now how absurd and even, I'll say, unappealing it is for a young man to claim not to enjoy eating eggs. How unbecoming pickiness of appetite is in a young man. Make eggs just for me then. You do know how to make eggs, right? There isn't an easier food in the world to cook."

"I think you just crack them in a hot frying pan."

"Put butter in the pan," Friis said.

"When the eggs are done," Anthonie said, "should I dump them on the ground and collapse and almost kill myself?"

"I've said it before," Friis said. "You're not without wit."

"Some people laugh. To get across the idea that something is funny, they laugh."

Friis leaned himself forward on the sofa and tried to shove the ottoman out of the way. He couldn't budge it.

"It's moving up my arm," he said. "The lack of feeling."

Anthonie moved the ottoman—it wasn't heavy. On the TV screen, a curvaceous Hispanic lady predicted a high of 79, strutting around in high heels in order to point out various townships.

"One week," Friis mumbled.

Anthonie didn't answer him. He watched the weather lady laugh about how much fried food she was going to eat at some festival.

"One week," Friis said. "No longer than that, you have my word."

"I heard you," said Anthonie.

"I'm at your mercy," Friis said.

Anthonie wasn't sure he could stand a whole week. So far, he'd been in this house less than a day. "Then what?" he asked Friis. "Then what, after a week?"

"I won't be your concern," Friis said. He found the remote on the sofa cushion and turned off the TV. "If I'm not on the mend, fine. Either way, I kick you out after a week."

Anthonie sighed. A week in the old man's clothes? He'd have to buy a phone charger. He'd have to get some normal food. Easy to forget, but he really didn't know this guy. "A whole seven days?"

Friis shivered, then attempted to pull his robe snug around him. When Anthonie saw he couldn't manage it, he grabbed a thin blue blanket off the arm of the sofa and draped it over the old guy's shoulders.

"It feels classless," Friis said, "to keep talking about money, but I don't expect you to donate your time."

"We're on the same page there," Anthonie said. "We can put the manners on hold for a minute."

"$200 a day. So, $1,400 plus what you already have. Help me to the bathroom and cook a little something now and then. That's all."

Anthonie filled his lungs with the stagnant, curry-tinged air of the house. He smelled a strain of woodsmoke from his fire last night. "This is weird, man."

"Oh, is it?" said Friis. "I guess I'm used to it. I ask near-strangers to cohabitate and nurse me back to relative health about twice a month."

"What the hell would I do? Like, when I'm not bringing you soup or whatever, what would I do?"

"What does anyone do? Read a book, watch TV. Take a walk. It's like a vacation."

Never been on one, Anthonie thought—he wasn't sure whether that was an argument for or against agreeing to this. Money was good. Money was always a sound argument. Anthonie tried not to think about the fact that this ancient grump would never have done something like this for him, or probably for anyone, if the situation were reversed. What he couldn't deny was a vacation—even this odd variety—would mean a break from truck fumes and jackhammers and panhandlers and rats. It would mean a break from his usual Wednesday morning gig unloading produce at Alifair's.

"I'm not giving you a sponge bath," he told Friis.

"Understood. No spa treatments."

"And make it an even $1,500."

"Done."

"Yesterday counts as day one."

Friis hesitated at this, but after a moment nodded. He raised his arm a bit, trying to prompt Anthonie to start their journey to the bathroom.

"One other thing. I want you to teach me something."

Friis narrowed an eye, skeptical.

"I want to know how to play chess."

"Oh, that's all," said Friis. "My pleasure. Consider it done."

"I mean seriously teach me, so I can be really good."

"If you're good at it, you'll be good at it. That's how chess is."

"Every day I'm here, you give me a lesson."

"I agree. I agree fully to these terms. Urination is a very pressing matter at his point—if we could address that next."

Anthonie gave Friis a finalizing nod and then went ahead and braced himself under the old man's delicate frame and hoisted him to standing, a hand on his lower back, a hand in his armpit. "So starts my vacation," he said.

After he'd crutched the professor down the hall—the same ten-minute hobble-stagger as the night before—and made sure the man was stable, two hands on the sink, and pulled the bathroom door shut, Anthonie returned to the common area of the house and went over to the semi-private alcove on the far side of the kitchen where he'd heard the message from Friis' daughter—a message, he guessed, the old guy wouldn't hear for a while. With what was likely the last of his phone charge, he called one of his roommates and made up a lie about going with some Wall-Street-type guys on a fishing trip to tote their gear and drive when they were drunk, told the roommate not to worry about rent—he'd have it on time. He called Alifair's and begged off for Wednesday, and then quickly shut the phone back off and took out his vape instead. He opened the window and paced out several deep hits, chasing away the small beginnings of a headache beginning to get a foothold in his temples.

There were two women he might've called, who probably wanted him to call, but he decided to save his last minute of charge. Neither entanglement was serious, and Anthonie wouldn't have minded either one ending. He wasn't going to come out himself and break up with either of them—not the nose-ringed girl who wasn't Hispanic but was in a Master's program in Latin American studies; not the Korean single mom who would often lapse into maternal concern for Anthonie's health and habits. He'd never been able to say no to women, but maybe a week without a peep from him would be a big enough hint.

After Anthonie made what Friis deemed 'an admirable effort' at scrambled eggs—the old man had no trouble putting away all three of them—Anthonie had to admit to Friis that he himself was in fact starving. Not for eggs, but starving.

"For what then?" Friis asked, wiping his mouth shakily with a plaid napkin Anthonie had provided with his breakfast plate.

"McDonald's," said Anthonie.

For a moment, Anthonie thought the professor was going to spit in disgust, right on his own rug, but it was just a sliver of toast stuck in his throat. When he'd worked it free, he asked, pronouncing the words slowly and with forced leniency, how Anthonie could choose of his free will to put that sort of rancid rubbish into his body.

"Why not?" Anthonie said. "That's the beauty of being young."

"It happens to be near your apartment and it happens to be cheap."

Anthonie picked up Friis' plate and carried it to the kitchen. He hadn't been able to scour all the yellow pigment from the grooves between the stupid fucking Mexican tiles. "How do you know I live in an apartment?" he called over his shoulder.

"You do, right?"

"Yes," Anthonie said. "I do." He returned to the living room and sat at the other end of the sofa from Friis. "And, yes, McDonald's is cheap. And also, it tastes good."

"You're paying them to poison you," Friis wheezed. "I guess it's good you're not paying much for that."

"Everybody gets old, no matter what they eat. Everybody slips and falls and has to depend on the...you know."

"The kindness of strangers?"

"Right."

"Streetcar?"

"My grandmother used to watch it."

With his good hand, Friis removed his glasses and held them toward Anthonie, his arm quaking like he was lifting a cinderblock. Anthonie took them and cleaned the lenses with a hankie from the coffee table.

"You kids might be street smart, but these corporations regularly play you for suckers."

"Is that right?" Anthonie handed back the glasses and watched the old man struggle to place them on his face.

"You want a burger? I'll tell you how to make a goddamn burger." Friis blinked, as if Anthonie had handed back his spectacles with a new prescription in them. "Get something to write on. In the drawer there. You're going to find out what a burger is. Take dictation, my lad. You're going on a grocery run."

"Sounds good," Anthonie said. "I can get some Coke."

The angular, yellow-sweatered young man at Surrey's Provisions—the white-collar version of a bodega—took the customer number Friis had given Anthonie without batting an eye. It felt surreal that Anthonie could get anything he wanted in this store, absolutely anything, and it would fall neatly onto Friis' tab and nothing else would be said; it felt so surreal, in fact, that Anthonie didn't grab one item not on the list. He found the fancy ground beef, the red onion, the vine-ripe tomatoes, the mayo in a little glass jar, the brioche buns, the soda Friis had grudgingly agreed to. The clerk did not watch him despite the fact that Anthonie didn't know where anything was and doubled and tripled back and forth across the store, a poor-looking kid in weird clothes. He didn't pay a bit of attention to Anthonie as he worked his way around shelves filled mostly with things he didn't recognize: quinoa instead of mac and cheese; beet chips instead of Lay's; organic granola instead of Honey Nut Cheerios; vegetables in funhouse colors—purple carrots and green tomatoes and asparagus in white and yellow.

The store carried a multi-device charger that would fit Anthonie's phone, and Anthonie stood in front of the rack and stared at the thing, it's black base and tightly wrapped cord, for a full minute before, for reasons he did not grasp, deciding not to get it. Deciding to leave his phone dormant. To call the decision odd was an understatement. What was this voice from deep inside him? This voice telling him to cut himself off, while he could, from the endless fast-moving river of electronic stimulation? Friis would not have objected to paying for it, so why wasn't he tossing the charger in with the rest of the haul? His face was hot suddenly. His stomach shrugged inside him. He would stay unconnected. That's what he was choosing. He would remain hidden out in the cold frontier, unaided by the tech world's instant answers. Its filters and algorithms. Its distractions. Its advertisements. What was going on with him, Anthonie didn't know. It felt strange, wrong, walking away from the rack. Walking out of the store. No charger. Driving home, walking into the house, no charger. Like he was a different person. Like his orders were being issued by a rogue authority.

Back at the house, Friis, from his headquarters in the slightly sunken living room, barked instructions—which pan to use, how much olive oil, how much salt and pepper and cumin to knead into the beef. He told Anthonie to let the patty sit 30 minutes, an unwelcome directive when his stomach was gurgling like a gutter in a thunderstorm. The onion must be thin. The tomato slice must be dried between paper towels. The bun required three minutes in the oven for slight toasting, while the cheese needed to be kept chilled until the moment of assembly. While Friis orchestrated the culinary proceedings, his voice was clear and resonant. Anthonie saw him closing his eyes to savor the aroma of searing beef, a smell driving Anthonie crazy by the time he plated the burger and came and sat in his spot on the sofa and took the first steaming, dripping, luxurious bite. Almost involuntarily, his animal self taking over, he dug into the next bite and the next, and felt the protein and silky fat filling the vacancy in his gut and the cracks in his psyche. He could feel the old man looking at him, and finally he turned toward him and conceded this burger was the best thing he'd eaten since his grandmother's fish stew.

Friis contained his gloating. He made a sign with his good arm toward the napkins, and only then did Anthonie feel the grease running down his chin.

"Don't forget to breathe," the old guy said.

Lopez de Santa Anna sold 29,000 square miles of Mexico to the US for 10 million dollars (the Gadsden Purchase), and was later banished from his country. The term 'ghetto' originally referred to sections of European cities where Jews were forced to live. The giant squid, which measures sixty feet long, has never been seen alive. Martin Luther started the Reformation in 1517—by century's end, most people in north and central Germany had become Protestants. Gideon v. Wainwright established a state must provide legal counsel for anyone accused of a felony who cannot afford a lawyer.

That night, in the study—what Anthonie had decided to call this chamber that belonged in the Harry Potter he'd read as a small child or the Charles Dickens he'd read as a high school junior—he explored the low cupboards behind the great, burnished chair and discovered two-thirds of a bottle of something called Calvados and a set of cut-glass tumblers. He poured two fingers—he'd heard older guys say that, "two fingers," on stoops and at block parties—and strolled about the room with it, listening, this evening, to something called Pavane pour une infanto defunte by Maurice Ravel. As to the liquor, Anthonie could tell it was pricey. He could actually taste it—though he couldn't have singled out a particular flavor—rather than just withstanding a chemical burn in his throat with each swallow, like when he accepted cheap shots at parties. Mineral notes. Something slightly sweet. A persistent mellow undertone rested on his tongue after each sip and for some reason made him think of horses. He'd never ridden a horse. Never even touched one, except a police horse at a parade once.

He idly pulled open the single drawer in the table the globe perched upon, and was all but staggered by the leathery, earthy, harmonious scent wafting up. There was nothing in the drawer but a sky-blue tobacco tin stamped with a plump yellow bird and, lying on its side but maintaining its dignity, a dapper pipe with a wear-shined bowl, a dark, contoured bit, and ivory accents along the stem. Anthonie took the tin in his hands like an artifact and cracked the lid open an eyelash. The incredible smell—roasted nuts, rain-wet lumber—intensified and along with the Calvados made him dizzy. He shut the tin and took up the pipe, lighter than he expected, and poised it in his fingertips by the bowl like Sherlock Holmes or somebody. He didn't put it to his lips. In the back of the drawer was a small box of matches labeled The French Laundry. Anthonie moved them about with one finger, then let them be. He set the tin back in its spot and then the pipe, then silently slid shut the drawer, indulging in a last deep inhale of the complicated fragrance.

He stood by the window, posing maybe, like a pensive rich boy at prep school, as the record offered the same song over and over, but performed by different musicians—one version more languorous, one sharper in the high register. When it ended, Anthonie, three apple brandies in now, started it over. He found he enjoyed the ceremony of placing the platter and grooving the needle, relished the anticipatory crackling preceding the first note. Liked to follow the slow, concentric journey the arm made—inward, inward. Again, like last night, the yearning arrangements created an atmosphere Anthonie happily surrendered to. Otherworldly. Contemplative. He sat down and let himself sink into the stately cowhide chair, feeling great inertia as the record played all the way through and ended and the player automatically shut itself off. Anthonie remained motionless, comfortably stunned, listening to the first calls of crickets and the final calls of birds, his brain slowed but not impaired. He felt something he couldn't name, and he had all the time in the world to feel it. He was in a state more peaceful than sleep, and he now saw a particular morning from many years ago. His grandparents' walk-up. His grandfather was sick—still alive, but with tubes in his nose and wheelchair bound, trying to talk about the baseball season even though it was February. Anthonie and his brother ate knockoff Fruit Loops with watered down milk. Anthonie's grandmother was fixing his sneaker at the kitchen counter by taping it from the inside. His brother's sneakers were new—acquired with money whose source would not be asked about. Anthonie was protesting, whining. It was about school. He wanted to go. He wanted to be there for a spelling and vocabulary test he knew he would ace. In PE, it was soccer day, inside on the basketball courts because of the snow, and Anthonie knew he'd score a dozen goals. He couldn't go to school that day because of his brother's hearing—hisschool, the middle school, was trying to expel him. Anthonie was ten, his brother thirteen. His grandmother was still strong—when she lost her breath, it was chalked up to age, the stairs—and wore the women's business suit she'd bought at a thrift shop for the sole purpose of defending Anthonie's brother against his own rule-breaking stupidity. No, they couldn't leave Anthonie at the bus stop this early. They were all going, staying together; she needed help with granddad. It was just one day. It was one single very important day so be agreeable. Support your brother. Show your brother you love him.

First thing the next morning—first thing after a trip to the bathroom—Friis offered chess tutorial number one. Anthonie couldn't very well beg off due to his hangover, so he went back to the study and fetched the set, balancing it like a huge tray of drinks and resting it on the end table closest the old man. Tea for the teacher and soda for the student. Anthonie had to rotate Friis delicately and prop him up with pillows so he could reach the board. His arm and leg were worse than yesterday, still immobile but now darkly purpled and swollen to bursting; he couldn't twist more than an inch at the waist, or really turn his head, but he did seem alert, present, no veil of pain partitioning him in his own world.

As Anthonie moved his hand from one piece to the next, resting his index finger atop each carven ally, Friis reviewed what each was called and the capabilities it boasted. Vertical. Vertical and horizontal. Diagonal. All three. How far each traveled. How valuable it was. The rook was more valuable than the bishop because the bishop was stuck on jade or wood, whichever it started on, all game. Both the rooks and bishops were more valuable than the knights, because a knight couldn't move all the way across the board.

"In what world is a bishop more powerful than a knight?" Anthonie asked.

"Knights save you from bandits. Bishops save you from eternal hell."

"Why is the king so weak?"

"Talentless as he may be," Friis said, "without him the kingdom is no more."

"What's castling?" Anthonie asked.

"Don't worry about that yet."

The professor said they should start playing, and he would explain whenever Anthonie made a suspect move. And explain he did. Each of Anthonie's first three moves were unsatisfactory—two were timid, and one showed no awareness of the move Friis had just made to free his bishop.

Friis leaned back ever so slightly from the board, reached deliberately to scratch his ear, then explained good players didn't make "dead" moves. The more you attacked, the more effort your opponent had to spend setting desperate traps.

"People sequester their queens, make them into fashionably late socialites, meanwhile the battle is raging and they're not using their best piece."

Friis shuddered with a chill, and Anthonie rose and stepped over and found the blue blanket and draped it over him. He picked up Friis' still-warm tea and moved it closer to him.

"Bring the bitch out, I say," said Friis, his voice wavering.

"Best defense is a good offense?" Anthonie asked, sitting back down on the opposite side of the board.

"A superior player uses your aggression against you, but a superior player will beat you, anyway. I'm not very good, so you might as well attack."

Anthonie gulped more of his Coke, trying to clear the cobwebs from his head. Soon he'd be hungry for something greasy. Something like that burger he'd made yesterday.

"You're not very good at chess?" he asked the old man.

"I have a worthy attention span and I've played a lot, but no—no real talent."

"Who taught you?"

"My uncle. He gave me this set for my 13th birthday. We played once a week. When I went off to college, I'd still never beaten him."

Anthonie lowered his attention onto the pieces and considered the implications of each of his possible moves—what each would allow him to do, what each would force Friis to do. He picked up a pawn, gripped it a moment, then set it back down. Picked up a bishop instead and angled it four spaces, into the center of the bord.

"How's that?" he asked.

"Too soon to tell," Friis said, "but that's the spirit. Get your boots muddy. That's what they're for. That's why they're not slippers."

After chess, full sun lancing in through all the back windows, Anthonie again hip-toted the professor to the bathroom and five minutes later dragged him back. Both men were left panting. With every trip they made down the hall and back, Anthonie felt he was hurting the old man worse than he already was.

"Listen," he told Friis. "I can get you a wheelchair for $75. Perfectly good wheelchair."

Friis scratched his chin. "How much are they if they're not stolen?"

"I don't know—a million dollars?"

Friis nodded. He had no grounds to argue, even if he wanted to; the trips to the bathroom were brutal. "Fine," he said. "You know where the money is."

"I'll make a call. I can probably get it today."

"Very well," said Friis.

"I'm gonna rummage for some clothes, too. We're the same size, basically. I need a shower. I need something else to wear if I'm going into the real world."

"You went to Surrey's."

"Right," said Anthonie. "I said the real world."

Friis nodded. "Maybe not ideal for purchasing contraband from a professional criminal, but there's a suit in there I hope you'll adopt. Smoke gray. Slim fit. Single-breasted. You'll see it."

"You want me to take your suit?" Anthonie said, as if anything this guy asked could be a surprise at this point.

"I vowed never to dress up again. After the party the other night, I'm all sweatpants all the time. I've knotted my last necktie."

"Sure," Anthonie said, keeping quiet his thought that the idea of Friis returning to campus to continue torturing his colleagues seemed farfetched at the moment.

"It's a perk," Friis said. "Consider it the cornerstone—"

Just then, he was interrupted mid-sentence by the hoarse trumpeting of the doorbell, which, from inside the house, sounded like the call of a diseased condor. Friis' eyes went round. He tried, unsuccessfully, to turn his head toward the front entrance. "Shh," he said. He attempted to raise his finger to his lips, but the result was a feeble we're-number-one gesture.

Anthonie leaned forward, peering up the hallway, and Friis motioned for him to stay still.

"Jesus," Anthonie whispered. "Is it your loan shark?"

"I don't know," Friis mouthed. "I have no idea."

The bell sounded again, raw and buzzing.

"Stay away from the windows," Friis said. "Go and look through the peephole. Careful—don't creak the wood."

Anthonie slowly rose, considering both the probability Friis was half-crazy and the certainty he had numerous enemies. He padded heel-to-soft-toe up the hall, past the lifeboat, past the frigate, past the schooner. With the patience of a burglar, he eased his eye to the cloudy peephole and took stock of what he saw there—a woman, maybe 35, wearing a bright green peacoat and matching hat. Average height. White.

He retreated to the mouth of the hallway and whispered his report to Friis, who looked puzzled.

"What color hair?"

Anthonie shrugged. "Brownish."

"Is she holding anything? Dropping something off?"

"A box," Anthonie whispered. "A cardboard box."

Recognition flashed over the professor's face, and then he and Anthonie both were startled by the third interjection of the hellish chime.

"For God's sake," Friis grumbled. "Take a hint."

Anthonie stepped closer to him, palms up in question.

"Does she have silly cat-eye glasses?"

"Yes, she has glasses. Who is it?"

"It's Sherrie, the Humanities secretary, or administrative liaison or whatever they call them. She'll go away. She's dropping off the Gulbinger essays."

"I think she's leaving," Anthonie said, craning his neck toward the cramped foyer.

"The incoming freshmen—first-years, they call them now—they write essays for a little scholarship and I'm supposed to select the least idiotic one. They're all about how Picasso was a chauvinist or Bach was a chauvinist or Hemingway was a chauvinist. They think that's what they're supposed to write."

Anthonie made for the door to retrieve the box, but Friis stopped him with a hiss. "Not yet," he said. "She could be lurking. She hates me because I refuse to make my handouts double-sided. I waste paper. It's roughly the same as being a pedophile."

Anthonie sat back down in his spot. "I don't understand why you keep working there, if you hate them and they hate you. Even the secretaries. Why not retire?"

Something evilly intelligent came over Friis' expression. Anthonie could've forgotten for a moment that the old man was hurt at all. "That's what they want," he said. "They'd love that—for me to let them off the hook now that I finally make a decent salary and they've run out of hoops for me to jump through."

"That's kinda sad, man. What's the point of having money if everything you do is just to spite everyone else?"

"Spoken like someone with no money," Friis said. "It's easy to say you'd act this way or that if you had money. Let me tell you something. The older you get, the less money matters. At the moment of death, I'd venture, it means nothing."

"I'll take your word for it," Anthonie said. "But I think there must be something you like about teaching for you to keep doing it so long."

Friis' posture stiffened, either with indignation or in response to a sharp internal pain. "Perhaps very occasionally," he allowed. "Perhaps every once in a blue moon a student finds his or her way into my class who's not wholly stupefied by 12-second videos depicting the lowest cultural denominators possible, a student not vehemently opposed to learning something without knowing precisely on which quiz it will appear and exactly which departmental learning outcome it addresses." Friis sniffed hard, then winced at the pain caused by the sniffing. "It's been a while, but it does happen."

By the time Anthonie's bus arrived in the nondescript semi-industrial neighborhood where the medical fence had his shop, he'd stripped his sweatshirt—the old man's sweatshirt—and was sweating down his back. He remembered the way—unmarked steel doors and ransacked newspaper boxes and shoes hanging from powerlines. He'd been right not to bring Friis' truck, old LC, down here. There were crews in this part of town who could strip a car to the chassis in the time it took to eat a slice of pizza.

Here it was. A round, green sticker on the door—Anthonie had no idea what the meaning of it was. He knocked and waited, and after a moment the deadbolt scraped and the door opened, a whiff of stale, rubbery air escaping, and a face appeared—the same guy from last time, with the hummingbird tattoo on his neck and slats cut in his eyebrows. He tipped his head questioningly without asking a question.

"Need a wheelchair," Anthonie said.

The guy recognized Anthonie, it seemed. He let him inside, but only into a windowless chamber with nothing in it. The guy left Anthonie alone a minute, then returned hefting in a metal chair and set it down roughly and unfolded it with a practiced flourish like someone doing a magic trick. Decent tires. Only one small rip in the upholstered seat. A bumper sticker on the back of the chair read It's Weird To Be The Same Age As Old People.

"One-twenty," the guy said.

Anthonie modulated the tone of his scoff—more surprise than scorn. "Last time you charged me $50. That was only five years ago."

The guy stared at Anthonie, trying to read him. Bejeweled sunglasses hung from the fence's collar. "I don't have a frequent customer discount," he said. "I don't do a punch card. Some chairs are more than others, like anything."

"I didn't bring a $20 bucks. I didn't even bring $100. I know there's inflation, but damn."

"Look, I got shit to do," the guy said. "I'll let you steal it for $90, but you tell anybody, I'll be the one knocking on your door."

"$60," Anthonie said.

The guy looked incredulous. "You're being rude. You're young—you don't know any better."

"You're probably right," Anthonie said. "I'm probably just ignorant."

"$80, okay?'

"$70," said Anthonie.

"Fuck me. You people think these things are delivered here with a bow on them? You think it don't take time and risk to provide this service?"

Anthonie draped the old man's sweatshirt over one shoulder and pulled out his wallet.

"$75," the guy said.

"Deal," said Anthonie.

The next day, after Friis and Anthonie breakfasted on toast and grapefruit—Anthonie only getting down a couple bites of the ridiculously sour fruit—and after Anthonie transported the old man to the bathroom and back in the wheelchair, both of them relieved not to cling to one another and drag themselves up the hall, the two spent several hours at chess.

Anthonie chose his moves briskly, imitating the men he saw playing in the park—the more confident Anthonie grew, the more circumspect was Friis, drawing a piece up into his stiff hand and clutching it a full minute before committing to an advancement or, more often, a retreat. Anthonie could detect little change in his host's injury level. A yellowish cast had perhaps suffused his eyes, and also the old man seemed to breathe more shallowly than before, not that he was doing anything requiring deep respiration.