Wake Island is a tiny island in the Pacific, operated as a communications base by the US. It spans only 2,500 acres and is some 450 miles from the nearest island and 1,500 miles from the nearest landmass. During WWII it became strategic to both the US and Japan as they struggled for control of the Pacific. Japan took the island from the US in 1942 and made POWs out of the 1,100 contractors there building fortifications for the US military. Most were sent to China as slaves. 98 remained on the island until the US returned, seemingly to reclaim the island, the next year.

A US carrier force, which included the USS Yorktown, arrived offshore of Wake Atoll on October 5, 1943. Rear Admiral Shigimatsu Sakaibara, who was acting head of the island, thought this armada included a landing force, and he decided the 97 contractors—and one doctor—still being held prisoner must be executed. "It will be quiet without all their complaining," he said to Lieutenant Torashi Ito, and both men laughed, but neither felt much like laughing.

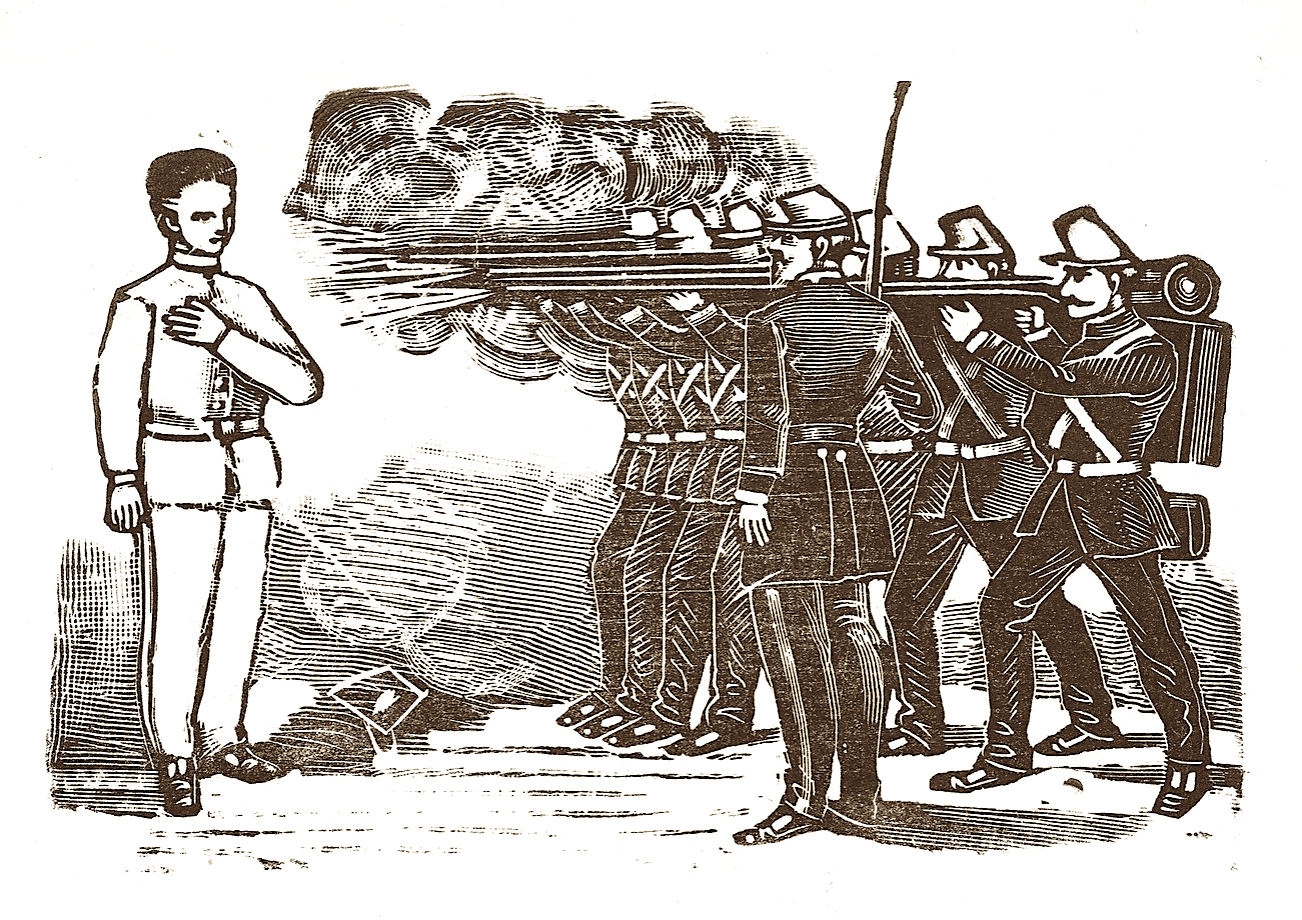

The POWs were herded from their barracks at dawn on the 7th. The US had been bombing the island for three days now, but there were no planes overhead. It was very calm. They walked under the eye of the latent machine guns to the lip of an antitank ditch (one they had helped dig), and many of them wept. They were blindfolded, their hands and feet bound. The signal was given. The men under Lt. Tachibana opened fire. The guns made a large sound, all encompassing, and it drowned out most of the shrieking. Soon the men were dead, and the Japanese soldiers set about rolling them into the ditch and covering them with coral sand. They shouldered their rifles and walked back to the barracks. Some of the men went to watch the offshore carrier force to see if anything had changed. Silence returned. The only sound was the occasional bark of the lieutenant's orders and the drowsy undulation of the waves.

Only Private Hideo Izchu had noticed Gary Drake fleeing the execution site, and he had not yet told anyone. Fearing what he saw was an aberration brought on by the grim intensity of the moment, he kept quiet.

Gary Drake went first to the barracks to grab his bags and cache of food, and then ran, always on the lip of the scaveola thickets, over the causeway to Wilkes Island, and hid himself inside an unused coral pillbox. There he sat trembling until the sun went down over the lagoon. No one came near him that night, and he slept fitfully beneath the pillbox. He wished he had a flare gun to signal the Americans.

At dawn, Private Izchu, after a night of fitful sleep, told Sakaibara he thought one of the Americans had escaped.

"Like hell," said Sakaibara.

"I think he escaped during the confusion, sir. There was much smoke."

"Like hell. We killed them all. There were no survivors."

"I do not wish to argue with you, sir, but I really think..."

"I am tired of this discussion. Would you like to dig up the Americans and count them?"

"Well, sir, I..."

"Very well. You will oversee the counting of the bodies—and heaven help you if they are all there."

Sakaibara gave the orders, and the committee set about the unenviable task of disinterment. Gary watched through binoculars from his pillbox. The work took several hours. He knew then he was in trouble. The soldiers laid the bodies on the sand like driftwood. He knew they had finished counting when two men looked up and began scanning the island and another started blowing his whistle and people came running from the barracks and watchtowers, some of them carrying machine guns. He was thirsty but remained in his pillbox. He was afraid he had left prints in the sand.

In the late afternoon he heard footsteps go by and men talking. The air raids began again just after sundown. He felt the ground shake with the force of the explosions.

The next morning, he crept from his pillbox. There was a faucet nearby in the shadow of a bunker. He drank as much as he could and filled up a coconut shell he had found before hiding again. There were more voices that day. The bombing stopped, and the next day he saw the carrier force was no longer on the horizon. He thought about killing himself.

He remembered the night he came to the island, when he and Babe and Halladay had grilled hamburgers on the beach (near where he was huddled now) and Halladay had built a great bonfire from dead scaveola branches and pallet wood and a ruined lifeboat that had drifted ashore from one of the carriers. Babe Hoffmeister, who had come here because it was dry, had still been sober then, and kept saying, "This is the happiest I've been since high school. Honest to God." Rainy had begun to cry (trying to keep it hidden) when the clouds over the lagoon turned crimson with the sun's setting. Gary had felt near tears himself, and when Babe asked him to toss the baseball with him, he had looked in the fire and said he would in a moment.

There was gunfire from somewhere on the other island. With the staggering profligacy of stars came more voices, distant, one in English this time: "American, you die tomorrow. This is not a big island. Cannot hide you forever." The men went away, and he slept briefly. He felt very afraid. He had been afraid for a long time.

His food ran out the next morning. He thought about returning to the bunker to retrieve some more, but he feared it would be guarded. He stayed where he was, hoping for rescue. It didn't come.

Three days later, emboldened by hunger, he went forth. He saw two men near his bunkhouse with their backs turned, guns slung over their shoulders, calmly smoking cigarettes, and he moved in the shadows until he was near the rear door.

"What was that?" one of the men asked.

"Shut up," said the other one.

He managed to grab two tins of biscuits and three cans of sardines (remnants of the Americans' food) before footsteps in the hallway scared him away. He went not to his pillbox now but farther south and pressed close to the wall of a bombproof, where he stayed for three more days. It rained on the second day, and he found a helmet and turned it to catch the rain. He had a good view of the lagoon from here. Sometimes they had played volleyball in the sand after work had ended for the day, the mess hall and the beach always full of music and people.

A great towering cloud rose over the lagoon, backlit by the oblique rays of the sun, insinuating more rain. He again turned the helmet over. He again had no food.

There was a food house near the causeway, and an hour before dawn, he left his cover and scurried past the bridge and into the woods and circled around to it. The rain never came, and the clouds moved off. The moon was full and cast a resonant light over the sleeping island, and his shadow stretched very far in front of him when he had his back to it. He ate in the food house and took what he could into his bag. There was a man standing on the bridge in the moonlight. Gary crouched under a scaveola tree and watched until it was almost dawn and the man walked past him, in the direction of the airstrip.

On the tenth night, he began to dream. He wasn't sure when he was awake and when he was asleep. He was standing with his ankles in the water and looking out at the lagoon. Halladay was with him, saying things that didn't make sense, and Gary told him if he weren't quiet, the Japs would come, and Halladay kept on, and finally Gary grabbed him and told him to shut up. He awoke on the beach the next morning, in the open, and had no recollection of how he got there. The next night he heard voices—American voices—and saw fire's light on the walls of the bombproof. The waves were very quiet, and he heard a voice he recognized but couldn't place, and then another, a woman's which he could, answered it.

"Lovely, isn't it?"

"Oh, yes. I wish we didn't have so much work though. Feels like we hardly get to enjoy all of this."

"Our shift is nearly up. Talked to Morris the other day. Said the airstrip won't take but another two or three weeks. We might have some time off before we leave."

"It's just so lonely thinking how far we are away from everything."

"I know."

He wondered how long it had been since he had talked to Rainy. Time meant less to him now, but he still thought it had been a long time.

His food was again out, and it began to rain. He was soaked. He had lost all concept of time. He had not stopped being afraid. The horizon was empty in all directions. There was only the lagoon and the dredging machinery for the submarine channel that now stood empty and the interminable blue of the ocean under the soft and immutable cluster of horizon clouds that would occasionally band together and rain on him. At night he would walk on the lip of the band of trees along the ocean, hiding and trembling when he heard voices, and in the daylight he would hole up in one of the pillboxes or bombproofs and usually cry himself to sleep. He slept very badly. His back hurt. He wondered where the American fleet had gone.

The Japanese had not forgotten him, but it became taboo to talk about him. Sakaibara sent out a small foray twice daily, but soon it became rote, part of the routine that governed every aspect of life on the atoll, and many of the men had begun thinking he had died. It had been nearly three weeks, and this was not a big island. Perhaps he had drowned.

He was in the food house when they found him. He had found some rope and was trying to decide how much of it and how many gnarled scaveola branches he would need to make a raft.

Stuffing several coils into his bag, he turned. Two men stood by the door, looking at him. No one said anything. One pulled a pistol from his holster and pointed it at him, and the other moved backwards through the door, his eyes not leaving Gary's until he was out of sight. Gary heard the man bellowing in the yard. Soon there was a great commotion, and the man holding the pistol grabbed Gary by the arm and pulled him through the door and into the yard. From everywhere, Japanese soldiers came running. Some were laughing and talking excitedly to each other, but most just looked solemn. He was led through the men to the captain's quarters, where Sakaibara had been at his papers.

Sakaibara rose when he saw Gary. Behind him on the sand, the gathered men grew quiet.

"You have eluded us... many days," Sakaibara said.

Gary said nothing. He was still thinking about the raft, about Halladay, about his mom back home in Boise where it was now coming fall and maybe there was even snow, and Sakaibara walked down the stairs towards the lagoon. Someone turned Gary in that direction, and he felt a gun in his back. He realized he was completely relaxed, for the first time perhaps since the Japanese had taken this island more than a year ago. He felt the muscles in his back loosen, and he smiled. When he reached the edge of the water, below the high tide line, he was forced to kneel. Sakaibara unsheathed his sword. Behind him were the scaveola trees. Gary realized they were probably not seaworthy. A cloud covered the sun.