There is nothing much to say about stage four pancreatic cancer. Any conversation beyond that pronouncement is just filler.

My son Bryan picked me up from the doctor's office, and together we went for Italian. The spring day was cool, the sky clear. I looked out the window and made a mental snapshot of everything I saw, from the young mother rolling her stroller along a suburban sidewalk to the way the still bare branches of the trees fractured my view. I hadn't told Bryan what the diagnosis was, and he took surreptitious glances at me as he steered the car around town.

Silence isn't like him, so I could tell he was worried. He's a person bloated with thoughts and opinions. Whenever you're speaking, you can see them just below his skin, bubbling, contorting his face, wanting to come out.

At the restaurant, I ordered a martini, which I never do, and then he understood. Or rather, to say he "knew" is more accurate, because how can he understand what I'm facing in a time when the idea of death has become an abstraction, when they've discovered immortality?

To be the last generation to die. Well. That's something.

The world going on without you after you die in all its petty marvelousness has always been understood, but it's different to know for almost everyone else it will continue forever, and it's only you, and others like you, who are missing out. The bell tolls for me, and not for thee, Bryan. Nor for our young server with her contemptuous indifference, or the couple at the next table with their two irritating toddlers. The bell has stopped tolling.

"We'll get you the best treatment, Dad," Bryan told me.

"The survival rate is five percent," I said.

He probably considered this another failure on my part. But unlike divorce, missing plays and recitals, and just being the tough son-of-a-bitch that sometimes passes for fatherhood, this wasn't a choice. There wasn't anything I could do.

For a long time, I think I was the best version of myself raising Bryan. I coached his soccer games and took him to the latest superhero movies. I'd ignore the complaints of my knees and back to play action figures with him down on the rug, even after an exhausting day when all I wanted to do was lie on my couch and watch the news. Every night before he went to bed, I'd call him over, look into those dark eyes of his, and say the words, "I love you."

Over time, you get lost and forget why you are doing the things you do. Sometimes we'd go to bed at different times and we'd miss our "goodnight." And later, when things were going south with his mom, he'd entomb himself in his room, his fury at the two of us barely contained by his closed door. Somewhere along the way, we stopped saying I love you.

"I have just one wish," I told him when he learned of my diagnosis. "Try to remember me as a good father."

"You were, and still are, a good father. And I don't need to remember you because you're going to beat this."

And I nodded and smiled because we all like to be lied to. Because I'm not going to beat this, and eventually Bryan will forget me. We'll all be forgotten, me and my last generation of mortals. What seems important now, the dying wish of a father, will seem no more important than whatever hopes you had when you blew out the candles at your fifth birthday party. How much memory can one mind hold? There will be lives within lives, lives blooming and then fading, the sediment of each covering the last.

How nice it will be for Bryan and those who live on to start over whenever they like, whenever life has taken a bad path, or when things have gotten dull and boring, because really, what will tie us all together now? Why should we have anything more than transitory relations, since spending eternity with someone, even your own children and grandchildren, will be too much? It makes you wonder what the point is.

Bryan is always on about some new scheme, buying the latest stock being hyped in his investing group chat, railing about fiat currencies, or trying to get me to go in with him on his friends' questionable startups. I love my son, but he's one of those who ten years ago told anyone who would listen that climate change wasn't real, who owned a big SUV just to make a point. But there's no denying the reality anymore. Now he tells me he's going to "win" the climate crisis.

"Dad, I have $50,000 worth of gold bars. Hidden. I'm not leaving it in a safe deposit box. And $50,000 in crypto that will go through the roof when things really start falling apart."

I wonder what good all those goodnight hugs and I love you's did. He's a great son, though, and he comes with me to my appointments, interrogating the doctors, bringing up points he learned on the Internet an hour earlier. I sit on the crinkly white paper on the exam chair, my shirt off, feeling like the old man I am, as the doctor, blank-faced, takes in my son's aggressive cross-examinations. Bryan being an asshole on my behalf is something I'll take. At the end here, I appreciate the days I wake up to the trills of the world's last songbirds, the blue of the sky as I walk through my neighborhood, and the taste of a beer on a hot day. But really, it's being around Bryan that matters. I won't die alone, I think to myself. Bryan will be here, and he's going down swinging.

The discovery was a way to renew your cells perpetually, to revert them back to an earlier stage. The process can also regrow limbs, hair, whatever. A constant renewal, a resetting of the clock, or at least that's my limited understanding. But some people, me for instance, are too far gone, and so we'll pass just like every generation before us.

You can still die if you step off the curb and get hit by a bus, slip in the shower, or you get shot by yourself or someone else. But if you manage to avoid these day-to-day American dangers and you receive the treatment every 15 years or so, you should be good.

It's a hard pill to swallow. The announcement came a few years ago. Bryan and I watched the televised press conference, amazed. A few egotistical billionaires, who figured they would haunt the rest of us forever, funded the technique. I'm sure they had no intention of sharing the discovery, but someone let the cat out of the bag, and rather than risk pitchforks and the guillotine, they opened the process to everyone. At a reasonable subscription price. So, nothing has changed. They're still billionaires, soon to be trillionaires.

"Dad, do you think this is real?" Bryan asked me, seated on the couch, beer in hand, as we watched a bespectacled young man in a white lab coat. He was flanked by two healthy looking tech entrepreneurs in their oxfords and vests. Behind them, through a clear glass window, was the rise of the now mostly brown Alps, with only the tiniest blots of snow on their peaks.

"I do," I said, because what would be more just than to condemn us all to perpetual life, just as life became unbearable?

"Would you do it?" he asked. "Live forever?"

And I said no, because it was easy to give that answer and easy to believe it. Because then I was a healthy 75-year-old man who could do 50 burpees and who still ran five miles every day. I said no because I didn't want some scientists with god complexes messing around with either my son's or my cells. Wasn't this the ultimate affront? Despite the acidic graveyards of dead fish, the unbearable heat, the hordes of migrants ravishing every continent, wasn't this finally the bridge too far?

I said no because I thought I could change my mind.

"I would," he said. And he did.

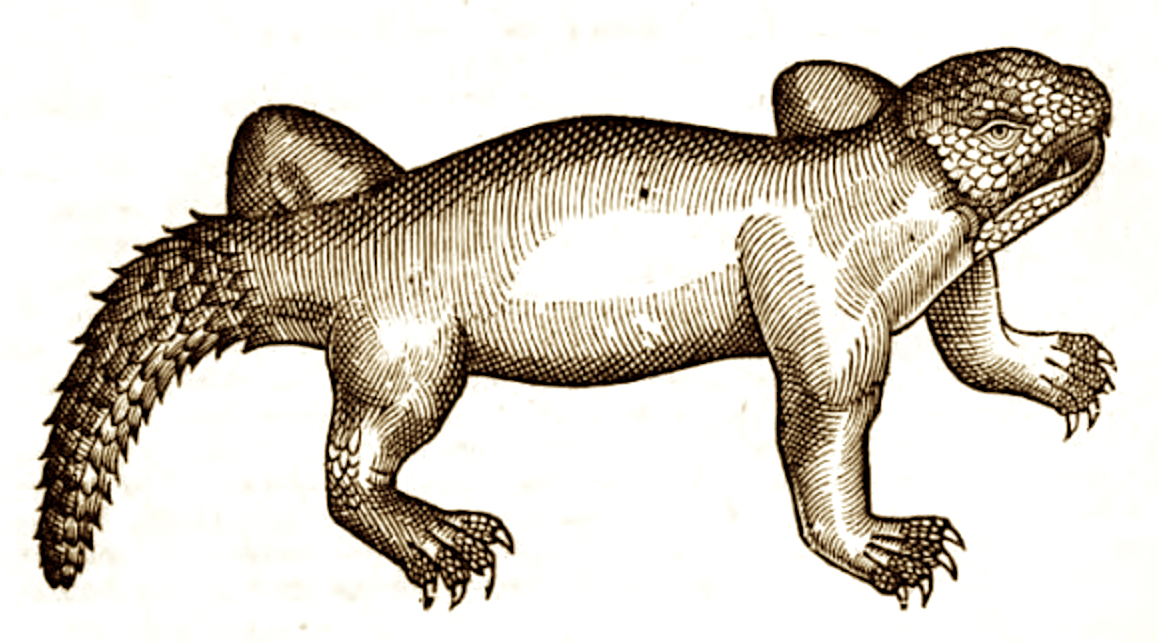

I went to the pet store and got a turtle. She was a little guy in a terrarium next to a couple of lizards and a tarantula. Pet stores make me sad. That I can walk in, pick up a dog, cat, or snake with no questions asked, is criminal. But then again, how much better would these poor creatures be out on their own, where their brothers and sisters are dropping by the millions?

The salesperson was a young woman in a blue polo with the store's logo on it. She smiled at me as I watched the turtle sit sage-like on its rock, unblinking, unmoving, its own experience of time so obviously alien.

"Turtles are actually really good pets," she said. "They're easy to clean up after, and they eat a lot of what you eat."

I tapped on the glass, but the turtle barely looked at me.

"Is this for a grandchild?" the salesperson asked me.

"It's for me," I said and tapped on the glass again.

"You know a turtle can live more than 30 years," she said, skeptically.

"I know."

"Oh!" And then she added, brightly, "So, you've gotten the treatment?"

"I'm not getting the treatment."

"Oh."

She sold me the turtle to me anyway, because what choice did she have? I can't have a turtle because I'm old? At least I'm not going to forget to feed it, or kick it when it's underfoot, or release it in the woods when I'm tired of it. If you're going to work at a pet store, then you're going to sell poor creatures to suspect people, and that's just the way it is.

I named her Minnie and built her a little environment, with Easter egg-colored rocks and a pool of water for her to swim in. I planted some hornwort and java fern that waved languidly as she stirred the surface. Her terrarium wasn't as large as I would have liked, nestled as it was on my bookshelf and right next to my television. I planned to take her out every day while the weather was warm to let her wander around the backyard, but I worried it wasn't enough and maybe she would grow bored or become unhappy.

But for now, she seemed content. I enjoyed seeing her there, paddling in her water, walking on her rocks, or just sitting. When I was first diagnosed, I'd had the urge to squeeze in all the things I hadn't done yet: parachuting, the countries I'd never visited, the great American road trip. Minnie let me consider the idea that it was okay to have days drift by, where the only productive thing you did was take a swim, or in my case, make yourself a nice Dagwood sandwich to eat out on your back porch, the sun on your skin, gnats looping in shafts of light, chipmunks and squirrels collecting acorns for some dubious future. An entire world can exist in a backyard, in a moment. I wanted to have as many of those little worlds as I could, while I still could.

Bryan wasn't taking the situation well. He came by most days to see how I was doing, bringing me my favorite cookies, asking if I'd like to rent a movie with him. Sure, I'd say, and we'd watch some war film, me on the couch, him in one of my dusty old wingbacks, Minnie swimming around in her pool just to the left of the television.

I only half watched the movies, more appreciative of the fact that Bryan was there with me. I hadn't had this sort of companionship since Bryan's mother divorced me decades ago. Back then, we went to the movies all the time, and of course I'd go to all his basketball and lacrosse games. The usual father-son stuff that can't help but create a tension. You can pretend you don't have expectations, but you do. They seep out of you as you stand on the sideline or sit in the bleachers, filling the air like a noxious cloud.

While we watched our movies, he'd glance over at me, as if he was afraid I'd fall asleep and never wake up. It was the same look he gave his mother and I when he thought we were about to get into a big fight. The truth is, I felt pretty good. Physically, I didn't feel much different than before, and I was still trying to keep up with my burpees and running. Some days I could, some days I was too tired.

"If we do the chemo, it may give you a few months," my new specialist told me, a young woman half my age with a matter-of-fact manner I appreciated.

"Nah," I said. "What's the point?"

Bryan finally let loose. We'd finished streaming some action movie that blared neon colors into the living room, with a body count in the 100s.

"Dad! You need to fight! Every extra day matters." And he gave me an angry look, which I understood. He wanted to wrestle the world into compliance, and here I was just letting it take me away. Letting it take me away from him.

"Have a drink with your old man," I said, and poured him a glass of the good cognac I keep. I wanted him to see it my way. I suggested we go sit on my back deck.

The sun had recently set, and the fireflies were winking in the shadows of my foliage. A scent of lilac floated on a breeze. I sat quietly, taking it all in, but Bryan was fidgety. He finished his drink and then stood up, leaning over the railing.

"Some things can't be fixed, son," I said.

"Dad," he said. "Give the chemo a try. Maybe it will give you some extra time. You know, they're getting better and better at the treatment."

I knew what he meant. He was hoping I'd recover, and then I could live forever. Like him. Bryan was divorced, with two kids about to go to college, and a girlfriend. I'd only met her once. He was worried about being alone, and suddenly I was a little worried for him, too.

"I'll think about it," I said. I didn't want to make my last days on earth miserable in the vain hope of infinite life, but I also wanted to reassure my son, to make him feel better. I wanted to protect him.

He looked relieved. This life is ending for you, Bryan. But you'll have another and then another, endless knots on a rope snaking into the future.

Shortly after that, I had an idea. I was back on the deck, this time on a misty, humid day, where the air made you feel you might drown. My backyard consists of a chestnut, a few birches, and a big sugar maple. It's ringed by a slatted, wooden fence with honeysuckle, raspberry and blackberry bushes lining it and filling the gaps between the tree trunks. But most of the yard is just open lawn—a blank space dotted by white clover, dandelions, and wild onions—that I mow but otherwise neglect. A local landscaper gave me a decent quote, so I told them the job was theirs.

"Listen," I said. "This can't be one of those jobs that just goes on and on."

The landscaper nodded, but I wondered if he heard what I was saying. My god, I thought. This is going to take forever, because forever is what this guy has. But, I hoped at some point he'd see I didn't have much time and take some pity.

"We'll start next week," he said.

That same week, we were hit with a heat wave that lasted for five days, blanching all the plants and trees in the yard, stunning the rest of us into a house-bound stupor. No climate control units were up to the task. I spent my days in my living room as close to the air conditioning as possible, watching TV and watching Minnie, who spent much of her time sitting in her pool, her mottled head and meditative eyes just above the water's surface. The heat was torturous, and I wondered what it would be like in the tropical parts of the world in another decade.

Once the heat subsided, the landscaper showed up with a crew of tanned men armed with spades, shovels, and a little Bobcat backhoe.

"Smart of you to do this," he said. "But why not a real swimming pool? Why a decorative pond?"

"I like to look at water," I said. "And it's not for me."

He shrugged and said, "A couple of weeks."

A couple of weeks wasn't what it used to be. But I felt okay.

"A couple of weeks is just fine," I said.

It was a hard two weeks. My body that had been merciful to me since the diagnosis, became a little less kind, a little cranky. Some days I couldn't get out of bed at all. Other days I felt well enough to take walks around the neighborhood in the evening's coolness, enjoying the feel of the asphalt on my feet, waving at my neighbors, watching their children play in their driveways.

The work in the backyard went on at a good pace, the workers in heavy cargo shorts and brimmed hats, sweat streaming down their faces as they hacked at the ground. I felt bad for them and left a big cooler filled with water, canned iced tea, and a variety of caffeinated beverages. I let them start their shifts at dawn, before it got too hot. Towards the end of the day, I'd fill the cooler with beer and drink a couple with them on the back porch in the shade of my maple, laughing and joking. Most of them were from Central and South America.

"What's it like down there?" I asked. They just shook their heads.

"Hot."

I nodded. The borders were closed these days, these poor workers' only connections to their families the remittances they sent. We all saw what was happening in south Asia and Eurasia, and nobody wanted that. Nobody knew what to do with these great floods of people escaping the ovens their countries had become. The suffering in some places was on a scale not seen since the mid-20th century, and we all knew it was going to get a lot worse.

Bryan came by to see me. The construction in the backyard mystified him.

"Dad, why are you building a koi pond?"

"It's something I always wanted to do."

"You never mentioned it."

"It didn't seem worth mentioning."

"I guess it's your money."

I knew what he was getting at, but I gave him credit for not pushing it too much. Indeed, it was my money, but I wanted him to be okay when I left. He made a good living, had his own savings, but now he would live forever.

"I've left it all for you. The house, a couple of million in stocks and bonds."

I could tell he wanted to say something about the chemo then. He got this anxious look on his face, and he balled up his fists, but then he just looked sad.

Later, when we were on our way to pick up some groceries and get a bite to eat, he told me about some investments he'd made. Clean energy and some defense firms.

"Prudent," I said. I looked out the window at the sprawl of nearly identical houses, the lawns browning in the heat, the sun glowing red just over the horizon. It's too late, I thought. But we bought our groceries, and we ate our burgers and drank our drinks like everything was fine.

The construction of the pond dragged on beyond the promised two weeks, extending deep into the slow death that is August. The heat was unrelenting, the bright, lushness of early summer giving way to deep greens and thunder-roiled skies. Mosquitos spawned in the hole in the middle of my backyard, buzzing in my ear as I sat on my deck. They didn't seem too interested in my blood, though, and I couldn't blame them. Nature knows.

As I watched the workers chew at the ground on days absent of torrential rains, I resisted the urge to hurry them along, to call their foreman or the owner of the company to complain. I channeled Minnie and her own unblinking patience. The want makes death real. The want brings it all down. So, I did nothing and just watched, chatting with the workers at the end of the day, enjoying the times when I felt okay, taking it all in as if my mind were a camera.

I went to see my doctor with Bryan, and she told me things "aren't looking great." These doctors really are masters of the bland euphemism. She didn't say "get your affairs in order," but she may as well have. She handed Bryan some information on hospice I saw him dump later into the garbage can in the parking lot when he thought I wasn't watching.

In the car he said, "Dad, we'll get a second opinion."

I shrugged and looked out on a day that was almost mild, a breeze blowing through my half-opened window, the weather relaxing its chokehold on all of us just a little. We all want a second opinion, but the verdict is clear.

"Maybe there is some non-invasive eastern medicine we could try."

This time I raised an eyebrow, listening to Bryan talk about eastern medicine, not the typical focus for him and his ilk of know-it-alls.

"Dad, you have to try something. You can't just give up."

"Acceptance isn't giving up."

"That's exactly what it is."

He pulled into my driveway. He turned to me.

"Dad," he said. "I love you. For me."

It was a dirty thing to say in that moment, but also a true thing. It was a chance to return to the better part of myself, when I tried every day to be the best father I could be for that boy. So, I said yes, I would get the chemo.

The chemo was scheduled for the next week, although both the doctor and I knew it was a waste of time. I was slowly losing my appetite, and I was feeling low and cranky. If I felt this badly now, I wondered how I'd feel after the chemo. I didn't want to spend my last days, holed up in my room, lying in bed trying not throw up.

I stood on my deck and watched my pond not get built. The day was a bright one with clear skies and no hint of rain, and yet the workers quit early because of unrelenting heat that was like Phoenix in summer, except with humidity. The way things were going, I'd never get to see Minnie out there in her new home, swimming happily, biding her time moment by moment.

I called the contractor.

"I don't have forever!" I yelled. "I don't!"

And then I was crying. Can you believe it? Crying on the phone with my contractor. I got dizzy and sat on the tiled floor of my kitchen.

"Just finish it. Please." And I hung up.

Later, I was watching Minnie. She was stoically sitting on her rock. Tomorrow she would sit on the same rock, and the next day, and the next. She seemed neither happy nor sad. She just was.

I called Bryan.

"I can't do it, son. I love you and I'm sorry, but I can't. Sometimes, it's just too late."

I hung up before he could reply. I couldn't take the chance. I figured he'd understand. Like I said, he's a good son.

They finally finished the pond. I found a landscape architect who came over and surrounded the pool with iris and eel grass. He lined the bottom with gravel and rocks, sank some water lilies to give it a natural feel, and floated some duckweed. I told Minnie she wouldn't have to wait much longer.

Bryan came over to see it. He walked around it critically, brushing his hand against the lilac edging its outline, kneeling down to examine the filtration system.

"I want you to do something for me," I said. I want you to take care of Minnie."

"Who?"

"You know. Minnie."

"Dad, turtles can live over 30 or 40 years."

"I know. But you have eternity."

I could see the gears in his head turning, of having to take care of something for such a long time, the anchor it would be on him. Good, I thought. A tether is what you need. Take care of something sensitive. Believe in something real. And fuck you for living forever.

I filled the pond with koi. The lilies and greenery around it glisten greenly in the humidity of the days, and butterflies and bumblebees do their work amongst the blooms. Dragonflies skim the surface, and I think I saw a little leopard frog the other day. I watch Minnie swim, sticking her nose up occasionally just above the surface. I found white eggs floating in the water one day. Egg laying is a sign of a happy turtle. I was glad.

Bryan watches her with me sometimes, a beer in his hand. I shouldn't drink anymore, but I do anyway. I enjoy his company, and the quietude of the day, time stretching in front of us, an infinity in each moment we are together.